“Dylan wanted to be here tonight, but not that badly.”

-Conan O'Brien, while hosting the 2025 Academy Awards

“I saw, ah what was her name, that lady, she had a beautiful voice. Shoot. Who was that?… JUDY COLLINS. I saw Judy Collins here.”

“My family took me to Riverdance here. It was amazing. Have you ever seen Riverdance?”

“Yeah, I mean no, I haven't seen it.”

“It was amazing.”

“I saw that show they do every Christmas.”

“The Christmas one?”

“Yeah…ummm… who was it... they do it every Christmas.”

“Oh I know who you're talking about I think.”

“Yeah, like each Christmas they come.”

“Skip Davis.”

“YEAH. Skip Davis.”

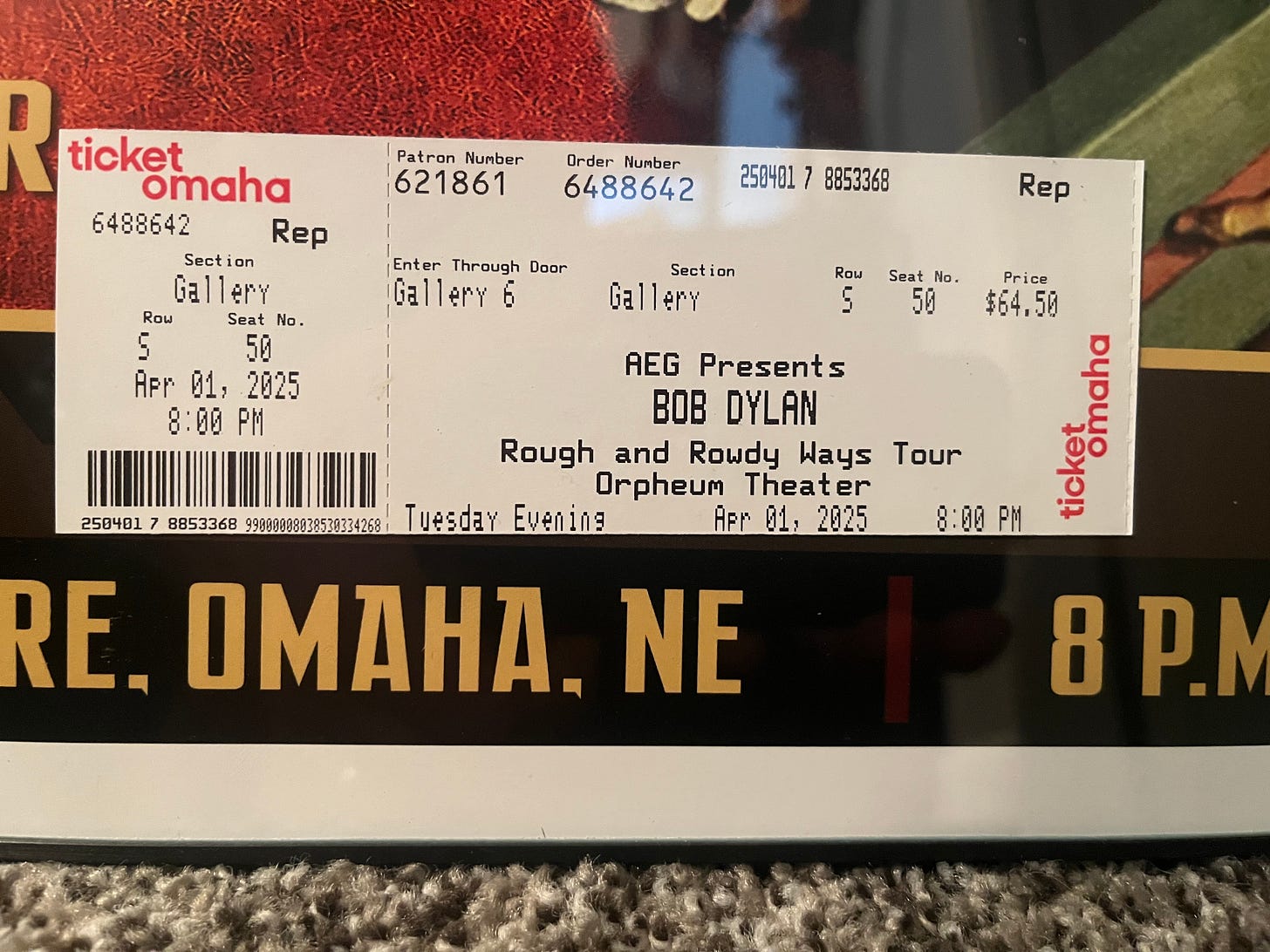

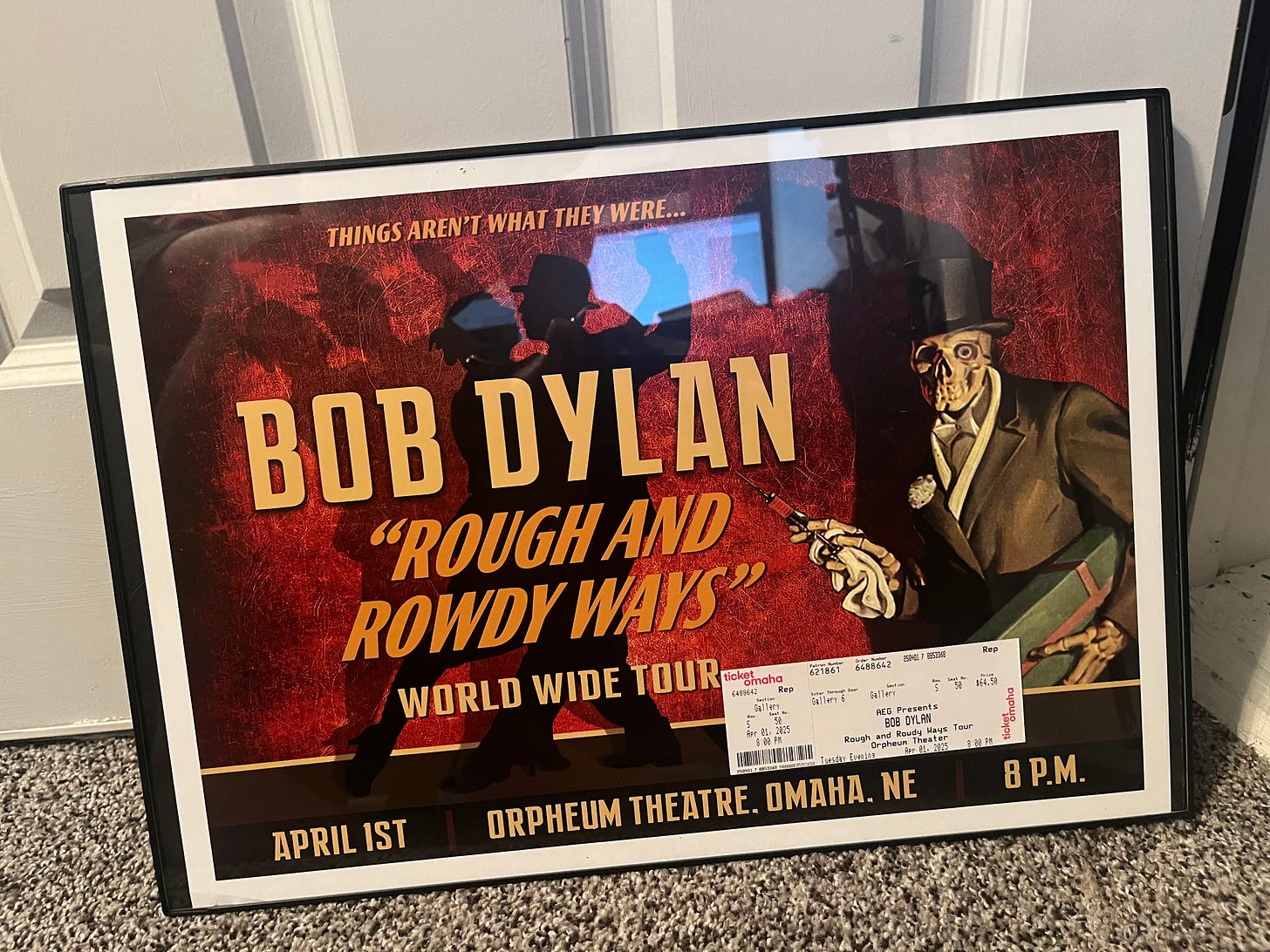

I needed an usher to help me find Row S Seat 50. The Orpheum Theater in downtown Omaha uses section names I'm not familiar with. Like cup sizes at Starbucks, each name means nothing in it of itself, but is chosen to mislead you into thinking that every seat is as important as the one in the section next to it. They aren’t. I was seated in “Gallery,” which translates to “Shit.”

Per Bob Dylan's request, my cell phone and the cell phones of all the other patrons had been locked in fabric pouches— eliminating them from distracting from the experience, or maybe it was to avoid unwanted recordings ruining whatever surprises Bob had up his 83-year-old sleeves. Either way, for better or worse, people were forced to talk to one another. In seats 26 and 28— the seats next to mine that for some reason only functioned in even numbers— sat two men that had spent many more years listening to Bob Dylan than I had. This was a special moment for them, a treat, someone truly great would have to be playing for these blue collar retirees to scrounge together $64.50 before fees and taxes to collect two Gallery seats in the very last row of The Orpheum. They reminded me of Statler and Waldorf, the grumpy old Muppets that sat in the balcony during Muppet Show performances and criticized how ridiculous and amateur all the acts were. But instead of unimpressed cynics, these two men could not have been more enamored.

“We came here in high school for one of my classes… my Spanish class, to see a play. It was that one famous one.”

“The Spanish one?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah I think I know that one.”

“Don Quixote.”

“Yeah.”

•••

I was there by myself. Tickets weren't cheap or readily available, and neither my wife nor I were really Bob Dylan fans. About a year ago, she found an old ticket stub her mom kept from when she saw Elvis play at the “Omaha Auditorium Arena” on “1976 THURSDAY Evg. Apl. 22.” The ticket was $12.50, which adjusted for inflation is about what my Gallery seat for Dylan was, only she was in the second row. I didn't grow up listening to Dylan, my only knowledge of his catalog were those songs you organically heard but never sought out. The kind where you ask, “who sings that again? ah, that's right.” But I knew Bob Dylan was a big deal. I knew it would be cool to be able to say I saw him.

I did my homework ahead of time. It wasn't hard, Timothée Chalamet had made Bob Dylan cool again. Shortly after buying my ticket, Paige and I watched the epic tale of Bob telling the folk music world that made him famous to go fuck itself. He wanted to use an electric guitar and play music that everyone at the big folk concert he was headlining hated. The drama makes you feel for Bob— the misunderstood creative that is fighting the establishment in the name of artistic freedom. A Man vs. the State type of story device, except the State is a bunch of humble, banjo playing, “aww shucks Bob wouldn't you like to just play the folk music, after all it is a folk music festival” kind of people. This system of oppression must be destroyed. And Bob Dylan is exactly the aloof don’t-give-a-fuck-I-do-what-I-want kind of man for the job.

In the movie, the hero prevails. Timothée Chalamet’s Bob Dylan shoved his electric guitar so far up Pete Seeger’s suspender wearing ass that the hillbilly sang his pussy folksy twang with distortion.

•••

I found a record of Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits and for weeks leading up to the show I played it on loop while drying dishes. I watched a Netflix documentary about some dope-filled tour Bob and his vagabond minstrel friends did. They played a bunch of music no one had ever heard and filled arenas so the world could get a glimpse of Bob. Martin Scorsese directed it— he just thought the whole thing was fucking great.

I liked the greatest hits album, at least a lot of it.

•••

I got to The Orpheum early. I brought a book and journal in my trendy shoulder bag, but my 21st century brain had been too hardwired for immediate gratification and short attention spans. With my phone locked in a fabric pouch under my seat, I was restless. I asked the usher if she knew where I could get a paper ticket stub, and she told me to ask the box office to print me one. I gathered three days of rations, wrote a quick last will and testament in case I was lost during the voyage, and threw down a rappel line from my Gallery seat to scale to base camp. The ladies at the ticket desk were real sweethearts. They were grateful and pleased to give me exactly what I wanted. I left them with a note for my loved ones in case I didn't return and started the trek back to the summit of Gallery Row S Seat 50.

I passed back through the phone line, but was expedited since my mobile device was still locked away. One middle aged woman spoke loudly to no one in particular. She adopted the kind of tone self-proclaimed expert travelers reserve for TSA officers after they’ve been politely asked to follow proper airport safety protocols.

“Oh, I’ve been to a Bob show before, I know how this works. I've been to Bob alright. This isn't my first time. Yup. I sure know.”

•••

The curtain was drawn and the sparse stage setup seemed in keeping with Dylan's sparse demeanor. A monstrous overhead tripod lamp was tucked in a corner, a steampunk industrial looking contraption that could have been a prop for a spotlight in a 60s era prison break film. A drum set was elevated on a platform and guitars were scattered across the stage, resting in racks and clumped together in several stations. In the center, was a monstrous grand piano. I wasn't sure what that was for.

I had ample time to study the instruments through the Bushnell binoculars I smuggled in next to the jailed cellphone in my shoulder bag. My seatmates were deep in thought— trying to come up with the other six times either of them had been at The Orpheum—when the spotlight clicked on, the house lights dimmed, and out walked a decrepit old-man, hunched over with a mop of graying hair. As he shuffled across the stage, his eyes never lifted from a spot on the floor three feet in front of him.

He sat down at the piano. Three men in stylish sportscoats and non-corresponding cool hats took their places at their stations. They moved a lot quicker than their bandmate. The no-names started in on a little ditty, but not one I recognized. I wasn’t alarmed. It's a common concert parlor trick to play your middle of the road songs early because the audience is just excited for the show to start. You save the big hits for later to give the crowd a jolt right about when the novelty wears off. The “I wonder when he is going to play…” anticipation builds suspense until the audience feels a cathartic release when the artist nonchalantly starts in on those oh-so-familiar opening chords. There's an exhale, a relief, a sense of I-thought-you-forgot-about-me-but-of-course-you-wouldn't-forget-to-play-the-song-that-made-me-fall-in-love-with-your-music. After all, how could he possibly forget? We hadn't hit that moment yet, the band was just warming up.

Bob started to play his grand piano.

“BLAM, BONG, BANG, BANGBANG-BANG—BANG, BLON, BLIM… BLAM—BLAM-BING”

Bob's piano was very hot in the mix.

“mmmb mmmbbbmmm and then we bought a truck mmmbbbmmbbmmm it cost more than a buck mmmmbbbbmmm”

And his vocals were not.

Ok, well an old man like Bob probably didn’t bother with a sound check and pianos are tricky to mic. It'll be better once he inevitably switches to guitar. That can't be long.

“BLAN BONG BONG BLAN-BING—BONG—BING-BING mmmbbb mmnnnmmm and then we got in the truck...mbbmmmnnmm BLAM BOB-BLAM mmbbbmmmm and the truck was on the road BLAM-BIM-BLAN”

The Julliard caliber backing musicians were locked into one another. The beret wearing drummer was a little high in the mix, but they were professionals. They got it dialed in.

“and then the truck kept driving BLAM-BING-BING-BLLLAN mmbbum we drove all day long mmbbb BING—BINGBING-BLOM mmbmmmm”

The only problem getting in the way was Bob's mumbling, wandering, mop of a head and his gorilla hands pounding on the keys.

APPLAUSE.

The opening song was over. A man four rows ahead of me stood in ovation, another from the adjacent section joined him. They were fucking loving it.

I waited for Bob to get up, pick up his guitar (acoustic or electric, I didn't care which) and keep the momentum going with one of his hits. The second song is usually a good time for one or those. There is so much excitement at the beginning that you can send the crowd into a frenzy with an immediate reward for sitting through the opening number. And come on, Bob has so many hits, it will take him a while to get through them all. He might as well get a couple done early.

“and then we got back in the truck mmbbbmrmm BLAN BING BONG the truck had a long way to go mmbbbmmmmn”

The two men sat back down.

This pattern repeated itself uninterrupted by any sort of commentary from Mr. Dylan. As soon as the truck ran out of gas, he found a fill station and got right back on the same interstate. Every fifth song the same man four rows in front of me stood up in a standing ovation, followed by his lackey the section over, and then they sat back down once the truck got back on the road. I was starting to get carsick, but not my seatmates.

“Did you recognize that one?”

“Huh?”

“Did you know that song?”

“Uh, I think so.”

“Yeah I think it was that ‘You and Me Babe’ one.”

"Yeah."

I wasn't sure either.

•••

The pattern was broken. Bob stood up.

Fuck yeah, here we go. Bust out that harmonica and let’s get this shit moving.

I hadn’t noticed before, but there was a reading light propped on the top of his piano. Similar reading lights were at the foot of each musician's station, presumably illuminating the night's setlist. But Bob took longer to study his than the cursory glance his bass player gave between truck stops. I grabbed my binoculars.

Bob was on his feet in front of his piano bench, flipping through a three-ring binder. He played the next song standing up, eyes reading from the pages.

“...the truck was a little old mmmbbbmmm BLAM BING BONG... the inside was yellow with upholstery and smelled a little like mold... mmmbbmm BLIM BANG- BING—BING-BING BLOM”

Guy four rows up stood and clapped, followed by his sidekick.

•••

When Bob addressed the crowd for the first time, I checked my wristwatch. He had played for an hour and 43 minutes before he said a word to the audience. He introduced each member of the band and then started the grand finale.

“I always loved that old truck mbbbmmm BLIM-BING I felt it had a lot of luck mmmbbmmm BING-BONG-BLAM- BING—BONG—BONG— BONG— BOO0OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOONNNNNNNNNNNNNGGGGGGGGG”

Bob stood up, backed away from his piano, and the crowd erupted. He hobbled like a movie monster, his gaze still fixed on a spot three feet in front of him. He walked to the back of the stage, made eye contact with the crowd for the first time, and allowed the audience to soak him in applause and admiration. He didn't speak. No “good night.” No “thank you.” He never once said the word “Omaha,” I doubted he even knew what city he was in.

He looked back down three feet in front of him and crept offstage. His band followed behind, leaving their instruments at their stations. The stage lights beamed as the applause crescendoed in anticipation.

And the house lights flicked on. My seatmates were confused.

"What? Is that it? They're not doing an encore?”

“Yeah, I guess not.”

“Huh.”

“Hmm.”

“Huh.”

•••

It took a while to get out of The Orpheum, the sold-out crowd bottlenecked to one of two stations where their phones could be unlocked. Since we couldn't yet retreat to our mobile devices, the concertgoers were forced to talk to one another.

“I didn’t realize he was such a piano player.”

I didn’t have that realization.

•••

As soon as the phones were freed, they were put to immediate use.

“Yeah I just got out… it was good... well it was a little weird, he didn't play a single hit... it was fun though.”

I suppose I shouldn't be surprised that someone who didn't attend his own Nobel Prize ceremony didn't really care about giving the crowd what they wanted.

Maybe it was that kind of attitude that made Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan. If he cared, he would cease to be Bob Dylan. But then again, how hard would it be to just play a song the crowd paid an obscene amount of money to hear?

As I was walking to my car, I saw Bob's tour bus pull away. He was onto his next show before I even had time to text my wife I was on my way home.

Whatever I thought about the concert, one thing was clear: Bob Dylan didn't give a shit.

After all, he's Bob Dylan.

It was cool that I got to see him.