"Dear Mis. Maxon,

I will miss you so much

if only you are staying

with us that would be

very awesome I will

always remember

you no matter

WHAT!

Love,

Rebecca (smiley face, heart)!

P.S. Good luck and I Love you a lot."

●●●

I’m not sure Mis. Maxon felt the same way.

I found this inscription inside a copy of Froggy Goes to Hawaii that my 5-year-old had just pilfered from a little free library on our dog walk. Grabbing a book was a reward. A bribe. It was about the only way to convince a kid to accompany me on my dog walks with minimal bitching (the dog is lazy as hell but walks further when a kid is with). It’s a cute book. A gift where you’d anticipate the: “I keep everything my students give me" teacher rule would apply. But somehow it was now in the Beaty family den as opposed to on Mis. Maxon's bookshelf. Maybe Rebecca never did her homework.

●●●

In his book Palaces for the People, sociologist Eric Klinenberg builds his case for designing physical spaces to encourage human-to-human interactions. He coined the term "social infrastructure" to describe what he was getting at. Just like a people need physical infrastructure for a society to function, it also needs avenues and anchors to promote social bonds. His favorite example of this: libraries.1

Not just because of the value of books, Klinenberg loves libraries because of their mission. The teleological aim of the facility. I recently walked into my own library and complained to the librarian about how I could never get the (otherwise fantastic) Omaha Public Library app to work whenever I stepped through their door. She shared my frustration, but also offered a rebuttal:

"Well, in defense of the library, it wasn't built with Wi-Fi in mind."

It wasn't built with Wi-Fi in mind.

What a pregnant statement. In today's age, almost a sacrilegious concept. Most structures—artifacts— of this pre-Wi-Fi era have ceased to exist. Their real estate underneath proven more valuable than their physical assets above. Bulldozed in favor of something "built with Wi-Fi in mind."

Yet, here this library stands, in no need of upgrades. And when my app fails to load the digital copy of my library card, I can just go up to the front desk. And talk to a person. A real person. Who will assist me with the same efficiency as a check-out kiosk and a functioning cell phone, yet with a pleasant little exchange that prompted several paragraphs of reflection.

Never was this need, this craving for human-to-human connection, more pronounced than (you guessed it) during the COVID lockdowns. I read Palaces for the People in November of 2020. The pages were thick with irony as the rest of the world was imploring me to never leave my house for fear of death.

“Social distance and segregation— in physical space as well as in lines of communication— breed polarizations. Contact and conversation remind us of our common humanity, particularly when they happen recurrently, and when they involve shared passions and interests.”2

This wasn't some pandemic manifesto like we see a lot of nowadays, Klinenberg wrote those words in 2018. Two years before some mutated virus jumped species and fucked us all up for a few years.

If he needed a case study to illustrate his point, the entire damn world became one.

I had checked that book out from a library. After months of closure, they finally worked out a system where you could borrow a book in 5 easy steps:

Reserve a book online

Drive to the library parking lot

Call the library on your cell phone

Wait for a masked librarian to deliver your books in a tied-up plastic grocery bag, strategically placed on top of a folding chair

Pick up your bag of goods, but only after the librarian was long gone. Retreated in fear of human interaction back to her cavernous library. Unfilled with people. And with shitty Wi-Fi.

●●●

Whatever they had in mind when they built this library, surely it wasn't this. Or Wi-Fi. Which begs the question, what was it built in mind for? I'll save some time here and just say “read Palaces for the People." But I think we implicitly know already. If you go to libraries, if you describe yourself as someone that likes libraries, then you know already. It's not just the free access to knowledge and entertainment, but everything the library represents. The children story times. The summer reading programs. The community gathering spaces. The book mobiles. The people.

There's no economic angle to libraries. They were famously bankrolled by Andrew Carnegie3 early on and now remain as publicly funded assets vital for a thriving community. In the book Freakonomics, economists (well one economist and one guy that was able to explain what the economist was talking about) Dubner and Devitt stated that the single biggest predictor of whether a child would be successful in life was whether or not there were books in the home growing up. Not whether or not the kids were read those books, just the presence of them.4 Klinenberg, it seems, makes the same case for a city and the presence of libraries.

Having a thriving library system says something about the city and its people. It says that they value literacy. Value access to knowledge. Value free speech, freedom of the press, and the pursuit of happiness. Value people. It’s easy to see how a city that holds these virtues would thrive in other areas as well— libraries were built with this in mind.

●●●

Our dog was a COVID dog and wasn't always this lazy. Unlike most, I actually lost weight during quarantine. I couldn't stand being in the house for long, so I took a lot of walks. Eventually, Mikko joined me. We had our standard routes. This dog was always stubborn. We usually headed toward the park, seldom made it all the way to the duck pond, and always mentally mapped out the location of every public trash can so I could throw away the thin plastic bag of dog shit dangling in my hand. But occasionally, very occasionally, we could make it to the little free library.

I always liked the idea of little free libraries but was disappointed with their content. I'm a non-fiction kind of guy. I get giddy with each new Walter Isaacson biography and was currently working through the complete works of Jon Krakauer. Those are not the kind of books that get paid forward in little free libraries. Romance novels. Books that someone from church gave you. Froggy Goes to Hawaii. These were my options. But I always checked what was inside when we could make it that far.

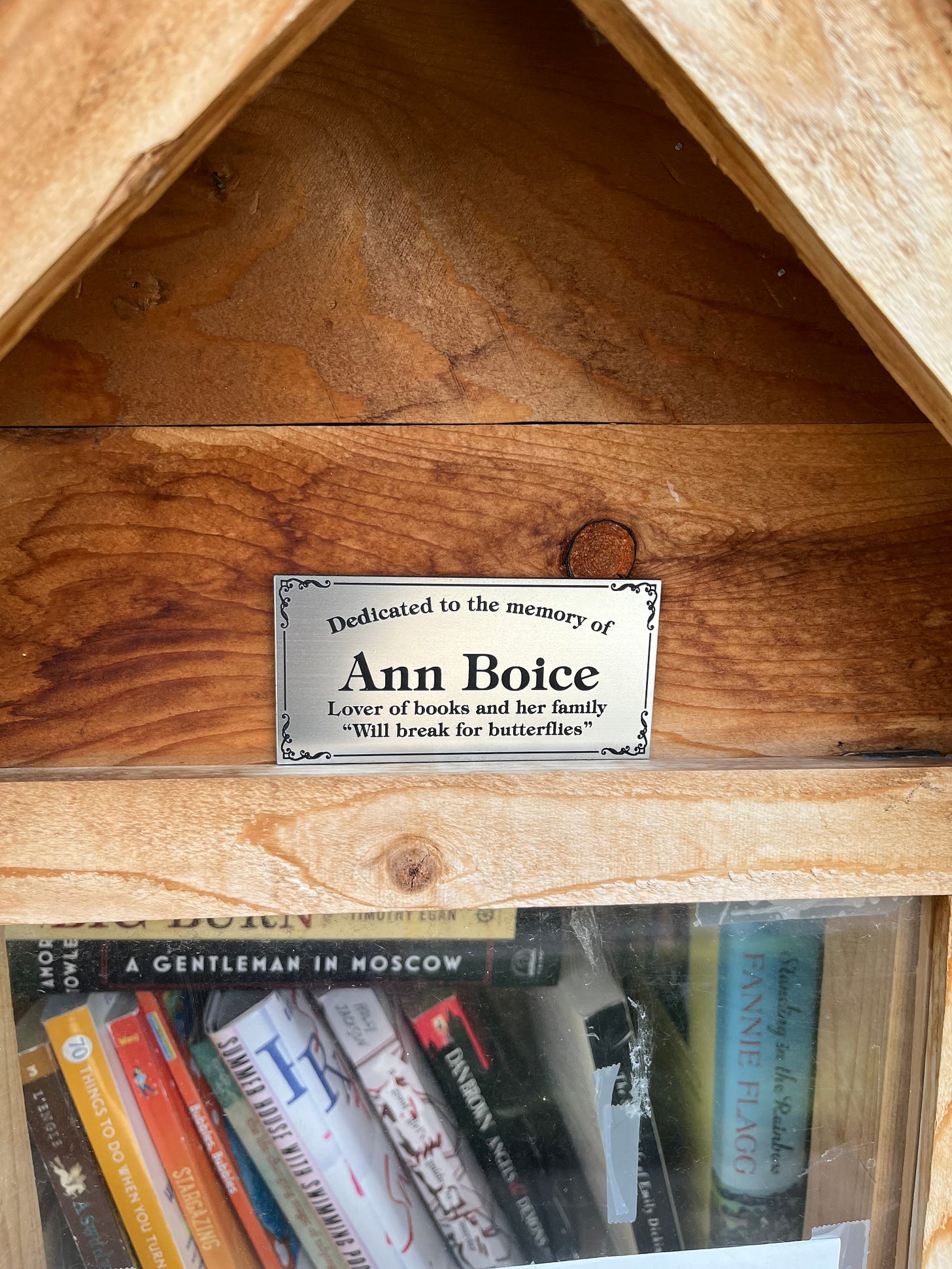

Our closest little free library was a legit one. It had a laser engraved metal plaque that identified it as part of an Omaha little free library system that someone maintained. I would often use it to recycle the dog training manuals and books from my mother-in-law. I think this is what most people did. That's certainly what Mis. Maxon did.

But within a span of a couple of months of dog walking, a few new little free libraries sprouted. Some literary pollinators had been circling through our neighborhood and seeds had been planted in the minds of my neighbors that we could use more of these. And my book options increased. Not necessarily improved, but at a minimum I had more landmarks to orient my dog walks around.

●●●

Of these new additions to our little free library system, my favorites were homemade. In the front yard, down the road from the retirement home dumpster, one in particular stood out. It wasn't the cold gray polymer that had been injection molded into a box on a pole, it was a work of care clearly planned out by the resident of the home. It was framed from lumber, expertly coated in scrap siding, and had an asphalt shingle roof that neatly hid LED solar lights that illuminated the contents at night. On the acrylic door was a handwritten note in perfect cursive encouraging you to participate.

I don't remember what the note said, but I took a photo of it. It was the first moment that I considered the story behind any of these boxes on a pole. It was something like, "books, like friends, are meant to be shared." I’m sure that’s not it and I’m remembering something from a t-shirt, but the sentiment was along those lines. It reminded me that it wasn't the books inside that made this gesture of sharing meaningful, it was the people that cared enough to share them.

So I always checked the contents. On one of these walks, I was caught in the act.

The owner of the home, and thus the little free library, and thus the books, pulled out of her driveway. She stopped in the street and rolled down her window. I prepared for a comment on how pretty my dog was (this happens a lot, he’s a damn good looking dog) but instead she had something else to share.

"There's a really good one in there called 'The River.’ I think you’d really like it.”

Well, thanks!

I snagged The River simply because I figured she might be checking later and I didn't want to let her down. I put it on my bookshelf for a while, and then put it back in a different little free library. I really wasn't interested in the book, but I appreciated the recommendation. Really appreciated it. Really appreciated that someone wanted to give it. Really appreciated that someone built a box and put it in their front yard just so they could give this recommendation, and others, to perfect strangers.

It was built with that in mind.

I was always a little nervous that this lady would stop me one day and ask what I thought of The River.

“Uhh, yeah it was awesome. That part about the river, yeah that was great."

But she never did. Her handwritten poem was replaced with a new note in her perfect cursive.

“New Books!"

Over time, the sun faded the ink, and the condensation wrinkled the paper. And then my favorite little free library got its own laser engraved plaque. But this one was slightly different than the others.

“Dedicated to the memory of Ann Boice

Lover of books and her family

Will break for butterflies.”

●●●

My library experience (big and little) changed drastically once we adopted kids. My wife had the idea that taking our newly adopted children to a Colombian library would be a fun activity for our first day as a family. Once we met our kids, it was very clear that this was a horrendously terrible idea. (In fairness to my wife, I initially suggested we take them to a movie theater and a Colombian soccer game that would have started an hour past their bedtime. We both had no idea what we were in for). My wife's first solo attempt at taking our kids to the Omaha library necessitated the assistance of a librarian to get our fucking kids back in the car.

So, we skipped libraries for a while. We've gradually reintroduced them into our rhythms a small dose at a time. Little by little so their bodies can build up a tolerance to the poison and not kill mom and dad. They're usually pretty fun now, but our dreams of what it would be like to take our kids to the library were more fun. But that's their fault, not the libraries’.

Instead, we took advantage of the remnants of the COVID era and started frequenting our blossoming variety of little free libraries. The one on the way to the park we nicknamed “the boring library,” but regardless we made a point to stop and browse. The reward for good behavior was the opportunity to take home a book. Despite the lack of provocative memoirs for dad to read, kid’s books were always plentiful. Suddenly these useful in theory but not useful to me structures were useful to me. And my kids loved them. I made a rule that Little Critter, Dr. Seuss, or Captain Underpants always comes home— which gave me my own quest when rifling through the stacks of otherwise forgotten pulp fiction. On one snow day in desperate need of an activity, my creative wife mapped out all of the little free libraries in our neighborhood and spent an afternoon driving the kids to every single one.

●●●

I had an English teacher that once said, "don't tell me, show me."

●●●

One walk to the park, my son and I did our routine pitstop at the little free library. I'm sure he grabbed some half-destroyed paper back copy of the latest Sesame Street hijinks complete with a well-orchestrated life-lesson. But for the first time since The River, something nudged me to take home a book for myself. But this time the nudge wasn’t from a pleasant old woman, it came from within.

I’m not sure who to compare my style of writing to, but David Sedaris always comes to mind. The problem with the comparison is though, I've barely read any Sedaris. I bought a copy of Me Talk Pretty One Day after that same English teacher mentioned how much he liked him. (I think he brought him up in class because he was flattered that the openly gay Sedaris inscribed, “I wish you were MY English Teacher“ during a book signing. Mr. V. was an attractive man in his mid-twenties). But after reading a few Sedaris essays in my newly purchased paperback, I moved on with trying to be an intellectual that reads things like essays and continued the tragic high school pursuit of trying to get girls to like me. I never finished that book. Or got any girls to like me.

If I had to choose which Sedaris book I would read first, I'd probably start with Naked and then re-attempt the volume that I discarded in my teenage years.

But there, in the little free library, was a Sedaris hardback I had never heard of: Theft by Finding. It seemed like the perfect name for a little free library book. I carried it home. I got to it eventually. The first thing I noticed was a stamp on the inside cover:

”Olivia Welts

19856 Sycamore Pl.

Omaha, NE 68134”

Who was Olivia Welts?

She lived in the same zip code as me, so she must have deposited the book on a walk. Why did she get rid of it? Did she think she would like it but didn't? One would imagine that if she stamped her name and address on the cover, she didn't anticipate giving it away. Above her name was an image of a honeybee. Why a honeybee? There are no beehives in our neighborhood, does she have some somewhere else? Does she just really like bees? Or honey? Or is it just the latest hipster animal, replacing owls and llamas? (When my wife and I were dating we would play a game called 'count the owls' when we went into hip, trendy stores).

I didn't know the answer to these questions, but it was fun thinking about them. In an age where I have a supercomputer in my pocket at all times, I kind of enjoy not knowing something.

As I read the book, I had even more fun. It was a collection of Sedaris' diary entries. I would have never checked this one out from the library, but since it had been a free acquisition I had little to lose. And it was fantastic. The book itself resonated with me and validated so many of the little oddities and observations that I have also pondered.

Even some of his anecdotes bizarrely mirrored my own. Sedaris talked about getting a typewriter. He wrote an entry about seeing old Playboy magazines at a barber shop. He wrote about Tijuana, Mexico and even talked about getting high on the day of my birth. (There was also an awful lot about gay sex and meth, so not all our Venn diagram of experiences had an overlap. You can't win them all.) It was one of my favorite books I read that year, and I had Olivia Welts and the little free library to thank for it.

Literary pollinators. Honeybee indeed.

●●●

Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of the Civic Life. New York: Crown, 2018. p.5.

Ibid, p. 176

https://www.nps.gov/articles/carnegie-libraries-the-future-made-bright-teaching-with-historic-places.htm#:~:text=Between%201886%20and%201919%2C%20Carnegie's,museums%2C%20offices%2C%20or%20restaurants.

Levitt, Steven, and Stephen Dubner. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York: Harper Collins, 2005.