"Dad, why do we celebrate October?"

"Do you mean Halloween?"

"Yeah.”

"There's something to do with it being the day before some holiday for Catholics, but I don't really know that part. Mostly we just do it because it's fun."

"Why do we celebrate Fall?"

“Do you mean Thanksgiving?"

"Yeah."

"Well, that one is a little weird."

●●●

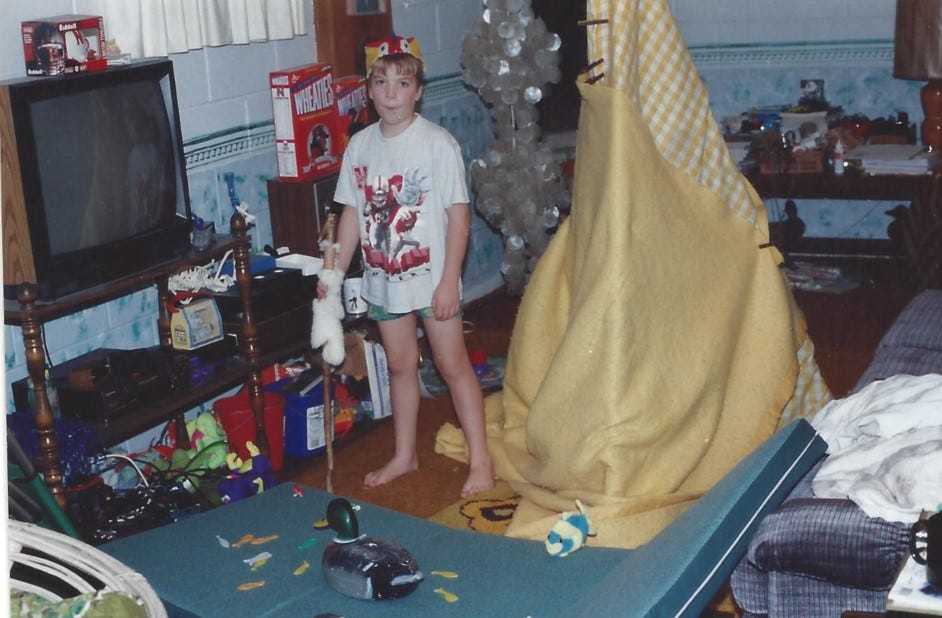

I spent a lot of my childhood playing with my friend Perry. Perry's favorite movie was the film adaptation of Huckleberry Finn, and he embodied the character. The two of us would create elaborate adventure scenarios down back alleyways, Perry’s grandparents’ cabin, Perry’s other grandparents' farm, and each of our backyards. We were seldom inside, but when we were we could be found in Perry’s basement junk room— digging through his dad’s old baseball cards and discarded collectibles the family had been meaning to throw out. The first time I was invited over to Perry’s house, the playdate ended with when his dad called the police to come unlock the handcuffs that Perry's little brother had fastened around his wrist. The cuffs were law enforcement grade, acquired during his dad’s time as a parole officer— but no one could remember where the handcuff key was.

Perry's little brother often tagged along, and he drove me nuts. I would sigh whenever his mom would insist that we include him, but we found a loophole to fulfill his participation requirements without having to play nice—we'd just make him the bad guy in whatever game we were playing.

Perry and I loved the classic role play of Cowboys and Indians. Perry always wanted to be the Indian, so I’d join his tribe, and we’d proceed to pummel the Cowboy played by his adolescent sibling. It wasn't clear why Perry loved the role so much, and his interest went beyond our improvised combat scenarios. He had collected an impressive display of replica Indian paraphernalia, mostly acquired from various gas stations or National Park souvenir shops during family vacations. Perry claimed he had some Cherokee blood and would give you the percentage of said blood upon request. I always had my doubts, but despite Perry’s pasty white complexion, his mom substantiated the claim.

But I really think Perry just liked rooting for the underdog.

●●●

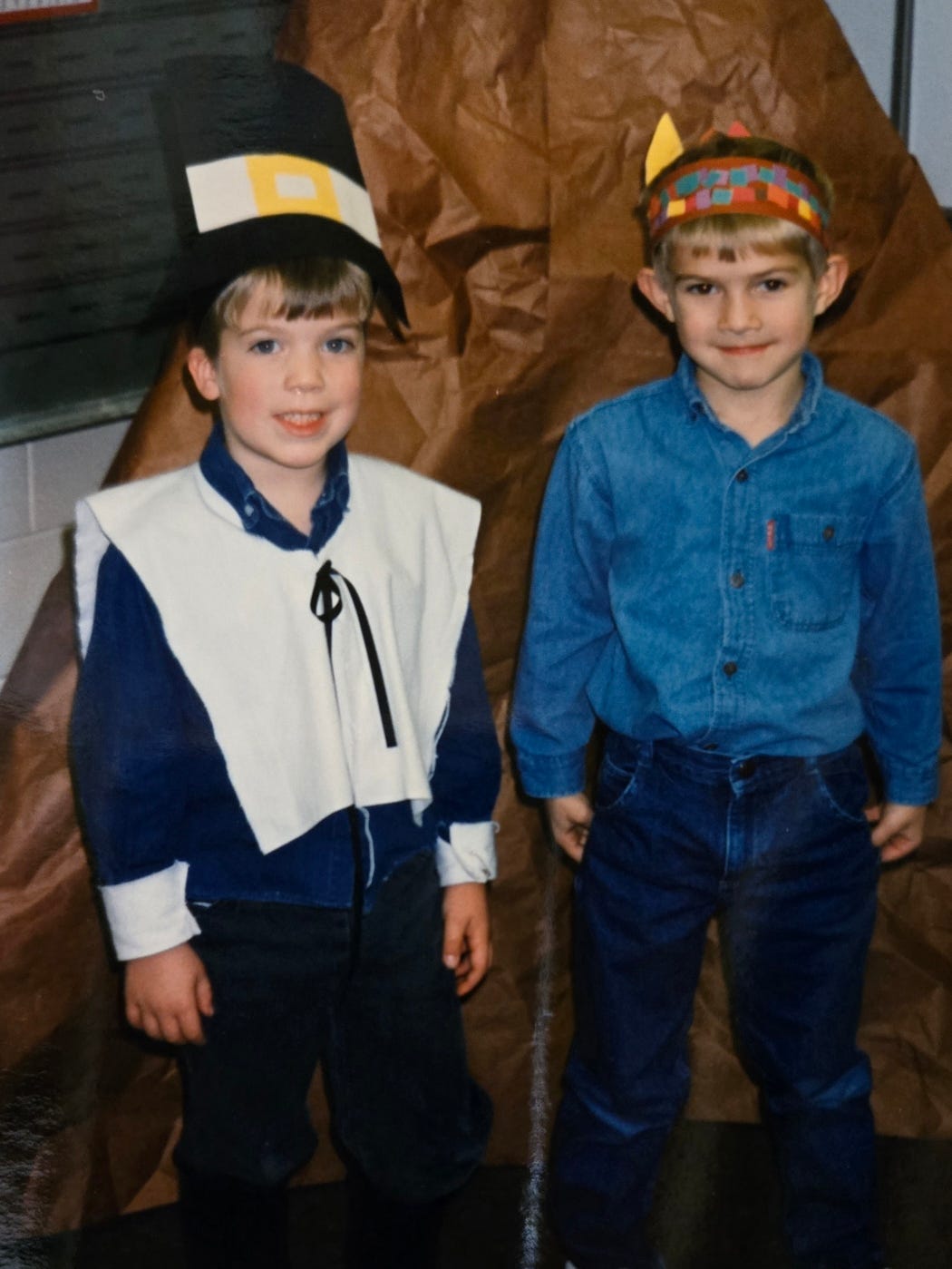

At our classroom Thanksgiving party, we were encouraged to dress up as either a Pilgrim or an Indian. I'm sure there was a goal of an even distribution among the Kindergartners, but the choice of attire was left to us and the Indians vastly outnumbered the white settlers. Predictably, Perry was one of them— but since his little brother wasn't around, I decided to align myself with the Pilgrims.

After all, we weren't meant to be adversaries—this was Thanksgiving. We were friends.

After all, isn't that what Thanksgiving is all about?

I wasn't sure exactly. I guess I'm still not.

The only other mention of pilgrims I’m familiar with is in John Bunyan’s complicated allegory Pilgrim’s Progress. I didn’t like that book, but I lied to a Pastor once and said I did. I had experience pretending to be something I wasn’t, even if that was the fan of an old book Christians are supposed to like.

I didn’t like the book Prevailing Prayer by D.L. Moody either, despite it being gifted to me by another Pastor as a present for helping with a youth group. I slogged through it though. I found Moody’s theology weird and troublesome, but he did have an interesting anecdote about everyone’s favorite seasonal gorging.

"It is said that in a time of great despondency among the first settlers in New England, it was proposed in one of their public assemblies to proclaim a fast. An old farmer arose; spoke of their provoking heaven with their complaints, reviewed their measures, showed that they had much to be thankful for and moved that instead of appointing a day of fasting, they should appoint a day of thanksgiving. This was done and the custom has been continued ever since."1

-D.L. Moody

That’s what Thanksgiving is all about Charlie Brown.

At least that's what D.L. Moody thought it was about I guess, but Moody didn’t cite his sources. And what about the Indians? Weren’t there supposed to be Indians?

To go along with the Pilgrim hat we made in class out of construction paper, my mom made me a Pilgrim shirt out of felt. I was proud of my outfit, no one else had cardboard shoe buckles.

I looked just like a Pilgrim.

●●●

The Boy Scouts knew that boys getting bored with camping was a real threat to business, so some Boy Scout intrapreneurs came up with a novel solution. Capitalizing on the popularity of secret societies and fraternal orders at the time, the Boy Scouts of America created their own Freemasons. They threw in some Indian stuff and The Order of the Arrow was born.

OA didn’t hide being serious and secretive, that was the whole point.

There were secret handshakes (your bottom pinky interweaved with the other guy’s bottom pinky if you were the lowest rank, and then you added another finger for each rank you moved up).

There was a secret code word that was only whispered directly into an ear and wasn’t supposed to be written down anywhere (“Ahoalton.” I think. I don't know how to spell it on account of the whole not being able to write it down thing.)

You even got a cool new Indian name when you reached the highest rank. The names were decided by a committee of other Vigil Honor Members after scrolling through a glossary of Lenni Lenape Indian language words. I always loved picking people's names. I’d look for the most ridiculous words and create uncomfortably long phrases that no one could ever remember. It reminded me of the movie Jungle 2 Jungle when Tim Alan learns that his son’s name “Mimi-Siku” means “Cat Piss.”

My name was “Malechinsin”, or it might have been “Machelensin”. I'm not sure which, it was written down different ways on the certificates I was given.

OA ceremonies were a big deal. We had initiation ceremonies and ceremonies for each level of membership. The ceremony’s content was also secretive, only those with the proper level of membership were allowed to watch them. There were four main characters in each, played by pudgy white farm kids wearing headdresses and regalia that cost hundreds of dollars and made up the entirety of an OA “Lodge's” annual budget. You could always tell which cities had the best OA Lodges based on how nice their headdresses were.

During Boy Scout summer camp, each Wednesday the OA would hold a “Call-out Ceremony.” All the campers for that week were lined up at the entrance to their campsite, and then a usually shirtless preteen dressed in Indian regalia would stand stoically at the front or the line— not flinching or saying a word regardless of how bad the mosquitoes were or how much you fucked with him. All campers, whether they were initiated into the Order of the Arrow or not, had to stand with arms crossed in complete silence. Eventually the four "chiefs" would walk in front of their campsite, and the guide would fall in at the back of the line with their campsite in tow.

More reverence was paid during this ceremony than the morning flag raising.

The Four chiefs— Meteu, Nutikiet, Kitchkinet, and Allowat Sakima— would read from a script (a couple of times my buddy Drew tried to memorize his lines for Meteu, but he was the only one). A list of names was "called out" to indicate which Boy Scouts had been elected by their Troops to join the Order of The Arrow. There was an initiation and some hazing to go, but otherwise the boys were now a member of our tribe.

The chiefs wouldn’t drop character until the costumes were off and neatly placed in their garment bags and back under the care of the Ceremonies Chief. Only then were we permitted to go back to our ordinary lives of white Boy Scouts camping for the weekend.

Well, most of the time.

There wasn't much to do in Grand Island, Nebraska. It became a tradition for Meteu, Kitchkinet, Nutiket, and Allowat Sakima to make an annual pilgrimage to the three holy sites of: Walmart, Bosselman's Truck Stop, and Tommy's 24-hour Diner. The chieftains were still solemn and serious while eating their late-night half stack of pancakes, but nevertheless these four warriors stood out amongst the late-night Grand Island crowd. We once saw the same man at both Tommy's Diner and later at Bosselman’s Truck Stop. I bet he gave his meth dealer a big tip after he started seeing teenage Caucasian Indians following him around.

I wore black and white face paint a few times, I even created a pattern that I wanted to be my signature Indian look. A middle-aged Scout leader who was heavily involved in OA back when he was a young lad saw my face paint and gave me an odd look.

"Didn't OA decide not to do face paint anymore out of respect for the Native Americans?"

It was a question.

I didn’t know the answer, I was as unsure as he was. He had thought he had heard something along those lines once, but he couldn’t quite place the comment.

I kept wearing the face paint. I thought it looked cool.

I’m not sure how prevalent Indian regalia is at the Order of the Arrow ceremonies nowadays— the Boy Scouts seem to have been making a lot of changes lately.2 But it does seem a little odd for a bunch of kids from farming communities dressing up like Indians, even if we did do it respectfully. Most of the time. Even if we were trying to honor their culture. Most of the time. A culture that wasn't ours.

●●●

I don’t know when exactly I realized that the term "Indian" was —at best— misleading and —at worst— offensive. It seemed to depend on the person you asked. And most of the people I asked were white.

I went to a presentation by an Indian—or Native American—or American Indian author who midstream launched into a George Carlin style rant about the names his race gets called. The limitations and inaccuracies of the term "Indian" are obvious, but he had his own issues with the term "Native American.”

“I'm not from America. That's not the name of the place where my ancestors came from. Then how can I be a native of a place that didn’t exist until white men came and called it that?"

Ok, I felt like he had a point, so then he was a Sioux, right?

"The name Sioux was actually a name assigned to us after white settlers asked a rival tribe what our people were called. The word they used meant “enemy” or more specifically “little snakes.” So, the French heard that word, but didn’t know how to spell it, so they gave it a French ending of “oux” and now we're known as the “little snake people.”

Well shit, that name was apparently worse.

I was waiting for the punch line of the speech where he blessed us sensitive white people with the official, politically correct name we could call “his people” and not be an asshole. But it never came.

To him, that didn’t seem to be the point. He didn’t seem to have much of a problem with someone who used the word “Indian” in a charitable spirit, even though it might be inaccurate. He was more annoyed with using a term like "Native American" or "Sioux" by people that were convinced they were being respectful.

At least that was his opinion. Which matters. But different people have different opinions. And those matter too.

●●●

It's not that we shouldn't change the names of our baseball teams, it's just that we shouldn't think that changing the names of our baseball teams makes us more understanding.

Maybe less ignorant, but not more empathetic.

●●●

Occasionally, I’ll arbitrarily pick a point in U.S. history and read a bunch of books about it. This past year I came across a copy of American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham.

I was perusing the shelves of a local bookstore, the kind of local bookstore where you feel obligated to buy something to help the underdog. I love biographies and have read some Jon Meacham in the past. I kind of liked those books, and this one had won the Pulitzer Prize—so I guess that’s good. I overpaid for the used paperback, and the volume sat on my bookshelf for several months until I reached the antebellum period of my historical curiosity. The book was great. I told my wife about it.

"Other than the whole “Trail of Tears,” Andrew Jackson was a badass. I can see why we put him on the $20 bill, even though everybody hates him now."

My wife offered, her response.

“Yeah, other than that “WHOLE TRAIL OF TEARS.”

I could see her point. But I elaborated.

"It's not that I don't think it was terrible, it just seems like it was inevitable. That's the pattern of history, people conquer other people. The idea that we were just going to share the land like we’re all friends just wasn't realistic. Jackson was just the guy that decided to rip the Band-Aid off."

She wasn't convinced.

"I suppose…"

I followed up American Lion with Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab by Steve Inskeep. I felt a little differently after reading that book. Maybe Jackson wasn't such a badass. Maybe he was just an ass.

Maybe the Trail of Tears is enough to determine your legacy.

Inskeep ended the book with his own interaction with an Indian— or Native American—or American Indian.

"…in our knot of walkers was Adam Wachacha, a member of the Council of the Eastern Band (of Cherokees). Wachacha said he had recently completed thirteen years in the U.S. Army. He was posted for a time at South Carolina's Fort Jackson, the name of which he found irksome… Serving in an army that flew Black Hawk and Apache helicopters, Wachacha was deployed to South Korea, where he was stationed at Camp Red Cloud. He found the army's profuse use of Indian names to be less offensive than the name of Fort Jackson and wasn't enthused about the general movement to have Indian names effaced. 'A little too much political correctness,’ he said."3 - Steve Inskeep

●●●

My wife and I like different kinds of books. It's rare to see me with a novel, it's rare to see her with anything non-fiction. But when she listened to the audiobook of Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann she acted as if Ingrid Michaelson had written a murder mystery about baking. She begged me to leave her alone so she could shove in her ear buds and listen to the systematic murder of Osage Indians for their oil money.

It seemed like the kind of thing I would read. It was. I plowed through the book version of the book with a similar fervor. When we heard Martin Scorsese had cast Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert DeNiro for a film adaptation, Paige made me watch the trailer on our basement flatscreen.

This story of “mineral rights,” exploitation, and land deals is fascinating and at times poetic. Sick of people forcing them off their land, the Osage Indians made the shrewd decision to purchase property that was shit for farming so everyone would just leave them the fuck alone. But in a cosmic sort of justice, the land they got off the discount rack happened to have some of the richest oil reserves in the country. Knowing their white neighbor’s propensity to take their stuff, the Osage leaders executed a brilliant maneuver— they allowed others to buy and sell the land above, but the Osage retained the “mineral rights” for anything found below. It turns out what was below was worth a hell of a lot more than what was above.

The Osage established a complicated system of “headrights,” which were basically shares of the oil business. Each Osage alive at the time received one “headright,” and when they died, the headright passed to their next of kin. An oil headright was absurdly ludicrous, and the white ranchers resented the red Osages for their wealth. They got out maneuvered. The white settlers weren’t used to this— it was the white people that were supposed to be the ones that knew how to trick people into shitty deals.

So, they decided to trick the Osage into some shitty deals, and when that didn’t work, they just killed them. Killers of the Flower Moon is about how a few swindlers married into Osage families, killed their spouses, and then inherited their headrights which granted them access to their oil money into perpetuity. It's mysterious, tragic, and disgusting. Many of these families live today still under the mystery of what happened to their relatives.

The book was so fucking good.

●●●

My family needed an affordable road trip, and we had done just about everything there is to do in Kansas City. After drawing a radius around Omaha in Google Maps, we decided on Tulsa, Oklahoma. I didn’t know anything about Tulsa, but the more we planned the trip, the more excited I became. I wasn't let down.

But despite how incredible the Catoosa Whale and the Tulsa Oil Man statues looked, we didn't quite have enough activity to fill our vacation itinerary. We looked for options in the surrounding Oklahoman metropolises.

"Where did all that ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ stuff happen"?

"Pawhuska"

"How far is that?”

"Not too far, we could do it on the way back.”

"Sweet, what about that Pioneer Lady that makes food out of sour cream, doesn't she have something in Oklahoma? Where is that?"

“Pawhuska”

"Looks like we’re going to Pawhuska.”

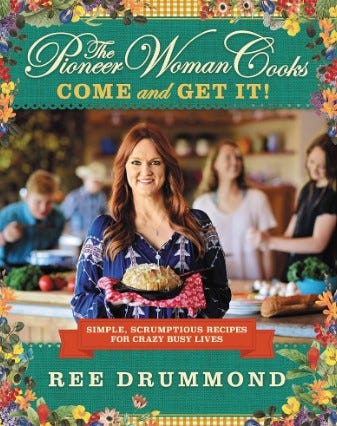

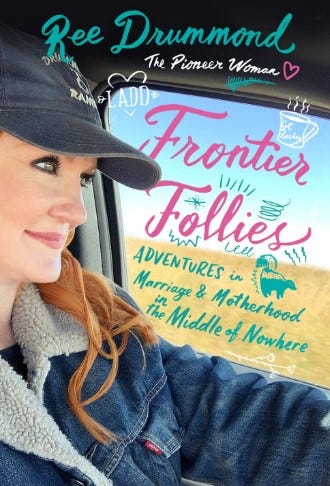

There isn't a lot in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, but the things that are there are owned by the Drummond Family. As in Ree Drummond. The dilapidated ranch town of fewer than 3,000 people has been turned into Pioneer Woman Disney Land. And the prices and lines to get to the attractions are just as exorbitant.

I felt odd about how overly commercial the small-town charm had become. Odd and above it all. I took cynical photos and sent them to my brother. Refusing to wait two hours to eat at the official Pioneer Woman restaurant, my wife and I found a small BBQ joint tucked away next to an abandoned railroad track grown over by weeds. This was exactly the kind of place I wanted to eat at in a city of 2,926.

We were enthusiastically greeted by the lady behind the BBQ counter, peering at us through stacks of Styrofoam cups that I would later fill with sweet tea. We were the only people in the restaurant other than this pleasant woman and a large man sitting in the corner watching a TV replaying a classic movie. It took us a while to settle on the appropriate amount of meat stuffs to feed our family of five— it was clear we had never been there before, and the restaurant's inhabitant was eager to help with suggestions. Eventually, the large man in the corner broke his silence and lifted his gaze from Clark Gable's overtures.

“Where you guys from?"

"Omaha.”

"Ahhh. Cornhuskers. I've been up there. You here to see the Pioneer Woman?"

"Actually, we're far more interested in the ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ Osage Indian murders," I said matter-or-factly.

I wanted to make it clear that I was a man of substance, not a man of frivolity. I wanted this large man in the comer to understand I wasn't in the middle of a pilgrimage to see the woman that taught the world how to make a quick and easy casserole with only four simple ingredients and 25 minutes. I was the kind of man that cared about culture. About history. The kind that read books.

The large man’s smile faded. His head dropped at the neck to peer at the floor. I hadn't expected this reaction, I thought I would have been appreciated. Respected. But I seemed to have offended him. When his head lifted again and his eyes met mine, I noticed his complexion for the first time. He wasn’t white. Which in Pawhuska meant he was Indian. Which in Pawhuska meant he was Osage. Which in Pawhuska meant the Osage murders weren’t some interesting unsolved mysteries. In Pawhuska, that meant the people murdered were his people. His family.

And I was taking my family to see the attraction.

He was kind. He told me there was actually a better book out there than David Grann's. I forget the name. But I remember the look on his face.

●●●

Pawhuska, Oklahoma has got to be the only town of 2,926 that has its own bus tour. Our family was the only one on the outing, but I found it fascinating. The driver was really excited about how they just got someone to make a DVD she could play to explain the stained-glass windows at the old cathedral, but otherwise the nice old woman drove us around and narrated the contents outside our vehicle. The Osage Nation is still deeply embedded and influential within the community—actively buying up land and other property. Property that was likely stolen from them a generation ago through one corrupt act or another.

The tour went a little like this:

"On the left you will see the Drummond Ranch, the largest cattle operation in all of Pawhuska. Ree Drummond married into the Drummond family in…"

"On the right you will see the tree where they would auction off Osage properties, the Osage people would get taken advantage of by…"

"Just ahead you, will see the old Walmart buildings that Ree Drummond purchased to warehouse all of the Pioneer Woman items to be shipped..."

"This site is where one Osage family was said to be murdered, so that his headright could be passed on to a wife…"

"Drummond…"

"Osage murdered so someone could steal their land and money...”

"Drummond…"

"Osage murdered so someone could steal their land and money...”

"Drummond…"

"Osage murdered so someone could steal their land and money...”

"Drummond…"

And then the inevitable —yet never suggested by our tour guide— connection crashed into my head as if our full-size van had hit a Drummond owned bison. I turned to my wife.

"Wait. Did the Pioneer Woman marry into a family that got wealthy from murdering Osage Indians?"

My wife offered, her response.

“Holy shit.”

●●●

While I ate my official Pioneer Woman pepperoni pizza at the official Pioneer Woman's pizza restaurant, the internet proved inconclusive. But suspicious.

There were a few facts that were consistent. The Drummond family were the wealthiest landowners in Pawhuska— completely independent of Pioneer Woman fame. The family went back generations, accumulated wealth over generations, and always lived in Pawhuska. There were numerous speculative articles written4 that pointed out dealings that weren't above reproach, but there was much more that was secretive. Though it was the most popular method of accumulating wealth in Pawhuska, the people that murdered and swindled Osage and stole their money didn't come out and talk about it. And the Drummonds had the most wealth. And had for a long time. There were enough questions for Bloomberg Media to create an entire podcast called "In Trust" investigating the Drummond family and their suspect dealings, which I listened to in its entirety once I returned to Nebraska.5 Despite the lack of evidence that may stand up in a court of law, it all just felt so painfully obvious to me.

I asked our Pawhuska Air Bnb host about how the community viewed the Drummonds. And the Osage.

She was a kindly cattle rancher, she spent her entire evening showing my children various horses, goats, and chickens while answering endless questions and acting impressed at my 4-year old's ability to mumble some sounds that were supposed to be the lyrics to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle theme song. She told one of her sons to go inside to find an old cowboy hat to give my boy. She encouraged her daughter to becomes pen pals with my daughter. By the end of our evening, I adored this woman.

Surely everyone in the community had already considered whether the Drummonds got their money from shady dealings and racist corruption? I figured she could put my mind at ease. There was probably an easy explanation, otherwise there would be more than just a speculative podcast out there.

She didn't put my mind at ease. She acted like she didn’t know much about it at all. Her understanding of the dynamic was just as flimsy as the flower patterned paper plates sold at the Pioneer Woman Mercantile. She didn’t try to sound authoritative, but her own explanations for how the Drummonds got their money were easily proven false by the simplest of googling. It's not that she was lying or trying to cover for Ree—she just hadn't put that much thought into it.

I guess not many had.

She did have a strong opinion on Osage politics though. She had thought about it a lot.

●●●

Despite the plausible deniability, I was convinced the Drummond family were racist crooks. Ree married into the family, so maybe she deserves some leniency, but it's hard to listen to the entire Bloomberg podcast and at least not feel a little reluctant to buy a festive cowboy themed crock pot from the official Pioneer Woman product line only available at Walmart.

“Paige. Once this movie comes out, the world is going to cancel the Pioneer Woman. There's just no way she could survive this. It's so obvious."

My wife wasn’t convinced.

“I'm not so sure. Her fans aren't the types that would care about something like that."

I could see her point. But I elaborated.

"Care about systematic corruption designed to destroy a race of people, steal their land, steal their money, and treat them as less than human? How could you not react with disgust?"

It turns out my wife was right. The movie came out. Unfortunately, it kind of sucked. And then everyone went back to not caring.

I saw that Ree Drummond recently released a memoir though. I haven't read it, but the cheerful cover didn’t suggest to me it was written by a sorrowful woman reckoning with her family's place in profiting from a genocidal cover-up.

I bet it has some fun recipes though.

●●●

No, I can't prove anything about the Drummonds other than to say, "listen to the podcast."

But I don't feel like it is wrong of me to at least care about what appears to be a complete injustice. What looks like a white family living in fame and fortune under the shadow of one of the darkest and most disgusting periods in our Nation’s history. Because appearances matter, especially when the rest of the culture refuses to look at them.

There are some character traits more important than being good at cooking a big fancy dinner for your family. Maybe we should care more about those values.

●●●

A pilgrim is "a person who journeys to a sacred place for religious reasons"— at least that’s my favorite of the six google results. If the Pilgrims came to the United States, and if that became their sacred place, then it makes sense that they would get together with a bunch of Indians who clearly felt the same about where they lived. It would make sense that they would both be thankful.

And it would make sense that they would both be at odds about it later. People aren’t good at sharing the sacred. Covetousness is part of the human condition. We are easily reminded of that.

But it’s hard to remember to be thankful. It takes effort to remember that. A holiday. A Holy Day. To remind ourselves to be thankful.

To be thankful for people that look different than us. To be thankful for the place that we live despite its hardships and inequalities. To be thankful for the things we have, and not the things we want to take from others.

Though I have to admit, it seems you have more to be thankful for when you look like a Pilgrim than an Indian.

Prevailing Prayer by D.L. Moody, pg. 57

https://oa-scouting.org/article/policy-update-changes-regarding-american-indian-programming

Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab by Steve Inskeep, pg.546-547

https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2023/10/the-strange-but-true-story-of-the-pioneer-womans-link-to-killers-of-the-flower-moon?srsltid=AfmBOooGhO909rTg9cXeSe84NsMfyWuZp-X4GopdBpLpIoBrH0QRlD5q

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2022-in-trust-podcast/