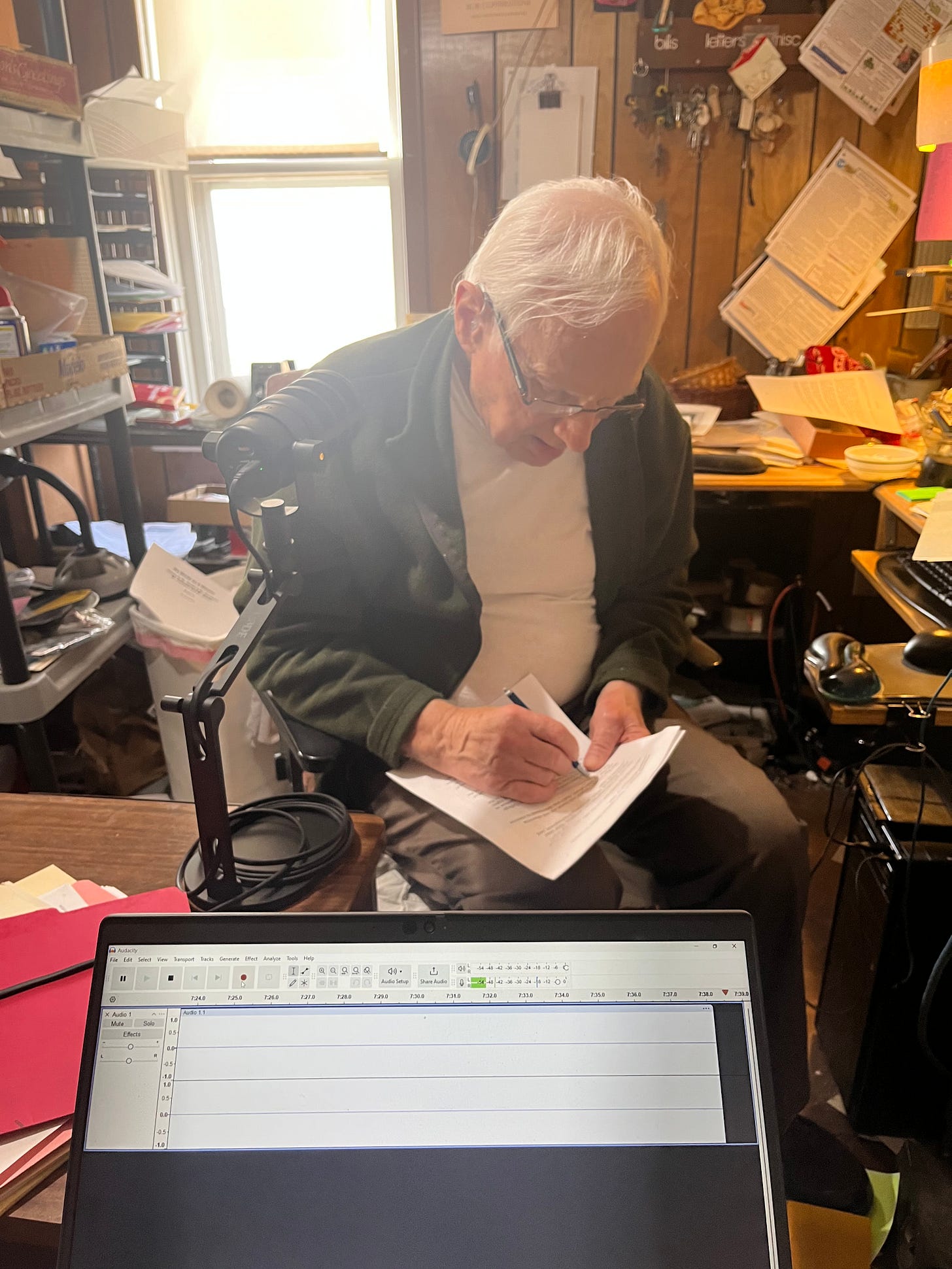

By Bob Copperstone

Having grown up in Wahoo in the early 1940s, it was inevitable that World War II would cast a somber shadow over my childhood.

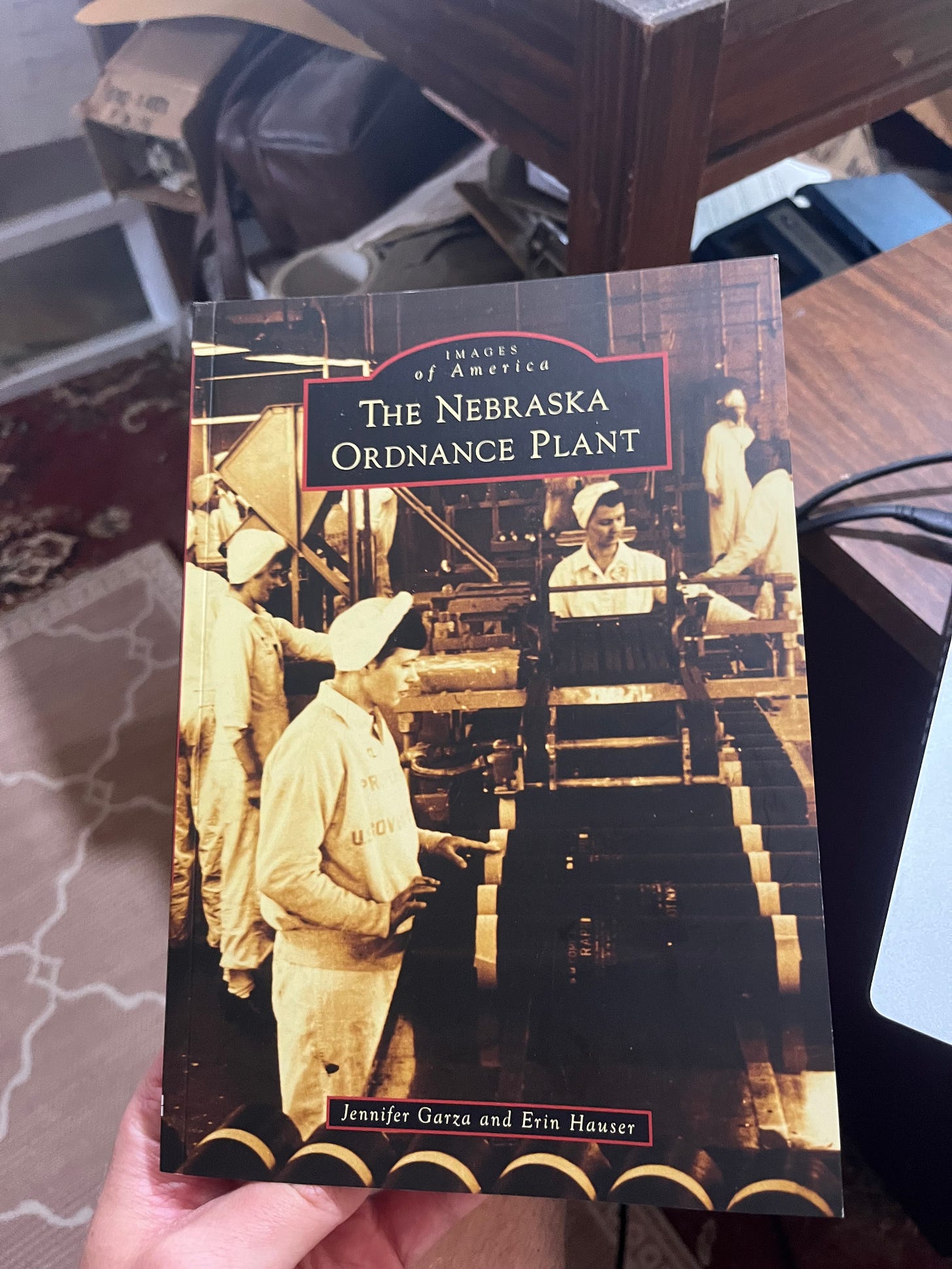

The Nebraska Ordnance Plant (“bomber plant” as it is still called) was near the village of Mead, a mere nine miles east of Wahoo.

It wasn’t talked about too much, but for years it festered in the back of our minds that our little dot on the map was certain to be in Nazi gunsights if Germany invaded the U.S.

The bomber plant gave a face to the undercurrent of a silent anxiety of war that hung like a noxious fog over many phases of our day-to-day existence.

Even though I had only a toddler’s understanding of that deeper fear, one day in about 1944, the NOP became the focus of a sudden family crisis.

My dad, Hank Copperstone, had hired on there as line foreman (his age had excluded him from the military draft.)

One day he came home unexpectedly in the middle of the day. The family gathered around him and everyone was very sad. We kids sensed the worry among the adults, and we were frightened.

Daddy was telling Mommy (Irma) that his production line had been improperly using a wooden paddle to stir the explosives, a process that made the job quicker, but was not safety-approved. Since he was a supervisor, they had to let him go.

To calm his children, Hank took us aside and, kneeling, explained sadly that Daddy had been “fired”.

After that day, I grew to adulthood with the entire family never letting me forget the time that little boy Bobby had inspected his father head to toe very closely before asking, “Daddy, where did you get burned at?”

* * *

Schools in Wahoo and other surrounding communities were strongly impacted by the NOP’s employees who lived on-site on Joyce Circle within walking distance to NOP.

Many children living there went to school in Wahoo and perhaps to other school districts in surrounding areas. I remember seeing Wahoo school buses on the gravel road (now County Road 10) that ran from southeast Wahoo directly to Joyce Circle.

Plus, almost everyone in Saunders County and nearby areas had friends or relatives who drew paychecks from the bomber plant.

The community had a nice little park in its grassy circle’s center, and there were occasional picnics and concerts open to visitors. My sisters were invited to schoolmates’ birthday parties there.

Some original homes remain today in private hands. Most are just as neat as they were in the 1940s and ‘50s. Some have added garages, sheds and other amenities. And there are still a few apparently abandoned houses.

* * *

The NOP was an enormous boon to Wahoo’s economy. I believe the plant had 24-hours of shifts. To accommodate them, the Wahoo, Chief and the short-lived Victory movie theaters offered first and second showings per night, and were frequently sold out. I remember the ticket prices were 25 cents for adults and 14 cents for age 12 and younger.

Also, there was briefly a USO entertainment center for servicemen (and presumably the NOP officers) with pool tables across the street west of the Wahoo Theater.

Almost no one today remembers the Victory movie theater any more. My own recollection is confined to watching a film short there about children with polio-ravaged lungs. The dreaded polio epidemic was in full force at that time.

The film showed an auditorium filled with row after row of so-called iron lungs. Children inside each machine were being kept alive and breathing. It made a huge impression on me. I didn’t want to be one of those kids! Was that my doom?

No one I talked to seems able to pinpoint the Victory’s location. All I can be sure of, it was somewhere off the northwest corner of Fourth and Linden streets. The theater just seemed to drift away after the war. I believe all three theaters were owned by the same pair of ladies, whose names escape me now.

* * *

After WWII, the plant’s massive bomb production waned, and the officers were reassigned and moving out of the Joyce Circle houses. It was a traumatic time for both the officers’ children and for the kids in Wahoo. They had practically grown up together.

My own family was caught up in the parting sorrow because my younger sister, Janie’s, best friend, Debbie Wallace, faced having to quit Wahoo High School and move away with her family.

But after much tearful deliberation, my family and Debbie’s agreed to take her in until she graduated in a year or so. It was traumatic for her to leave her family, but the plan worked out fine, and she graduated with Janie in 1959.

The Copperstone family’s connection with the NOP was quite strong. In addition to taking in Debbie, two years earlier my older sister Rochelle’s good friend, Bonnie Prior, roomed with us on weekday nights all through high school until graduation in 1955. Bonnie would go home on weekends.

And I learned recently that another NOP family had worked out a similar plan for their daughter. The girl finished out her high school senior year by renting a long-term room in a local motel, joining her family after graduation. I never discovered her name.

My late uncle Audry (sic) correct spelling) Copperstone, who began working for Firestone at the NOP as a firefighter in 1943 until it closed in 1963, was one of the few local NOP employees who was able to keep his job, since fires are a constant danger regardless of the presence of humans.

* * *

The huge tract of farm land that was gobbled up by the NOP as a sacrifice to the powerful and soundly successful “war effort” has mostly been returned to both private use and for the University of Nebraska experimental agriculture purposes.

Gone are the armed guards at the former entrance gates, as are the half-dozen or so water towers that once dotted the skyline almost from horizon to horizon. Only a few towers remain. The massive complex of buildings that were occupied by throngs of workers has disappeared.

I am among those who innocently continued to live near-normal wartime lives while the enormous war machine that was the Mead Ordnance Plant was born, and thrived, and then died. My far-from-perfect memory, and that of others, can capture only a tiny slice of its complicated, massive history.

Surely, today there are locals like me who retain memories of the NOP’s wartime past, and I wish I could hear all of all of them. Unfortunately, we such humans are no more permanent than the bomber plant itself, or than the untold thousands of bombs made here that were dropped to win the war.

But fortunately, the nuts and bolts of the bomber plant, from inception to operation to the wrecking ball, have been captured for all time by a rich collection of photographs, newspaper articles and museum memorabilia.

If only human memories were not so fleeting.

* * *

Because of our fading memories, and the decline of the populace from that era, we seem to have arrived at a sort of forgiveness for the minus sides of the NOP. But the minuses sometimes bump up against actual facts and work against total truce. The minuses include:

--Landowners were forced by eminent domain to sell their land on the false promise that they could buy it back after the war.

--And toxic waste was recklessly dumped on the NOP over the years. To this day, another war is being waged on poisons that lurk in the wells, streams, air and soil around Mead, foiling all efforts to find an effective solution. So far, we are losing this war.

--Also, perhaps emulating the bomber plant’s poor examples of waste disposal, bad actors in recent years followed the government’s muddy footsteps. They dumped poisonous herbicide filth on that same once-arable soil around Mead, in pursuit of quick profits from dirty-fuel ethanol.

* * *

Today, while reviewing my recollections, I realize that one of my own personal bomber plant complaints has been festering for some 78 years, so I suppose it’s time to follow the example of forgive and forget.

OK, Uncle Sam, I forgive you for burning my Daddy.