Warning: This story contains depictions of the deaths and tribulations of cute, fuzzy and feathered little creatures. Children, non-farmers and other super-sensitive individuals may be offended by exposure to the real world.

By Bob Copperstone

Chickens -- the raising of them and the eggs from them -- played an outsized role in my boyhood in mid-century Wahoo.

Some of my recollections are pleasant. Others, not so much.

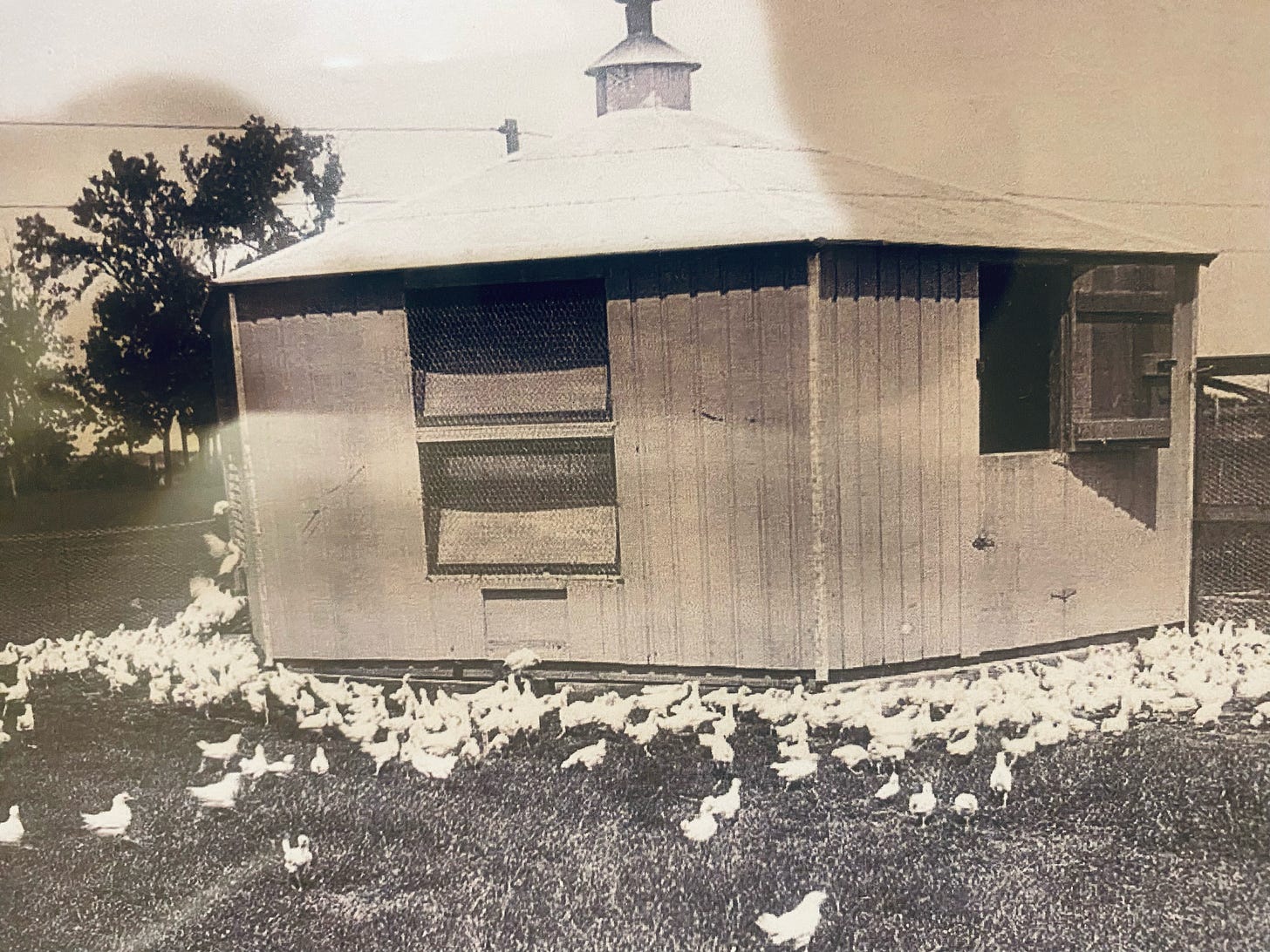

Those fowl memories occurred at my Aunt Clara and Uncle Jerry

Bartusek’s farm north of Ceresco, where I spent many a summer vacation.

Feeding the chickens was one of my chores, hauling buckets of feed around the barnyard. That was pleasant enough, watching the eternally hungry and ever-grateful flock come charging at me in a clucking and screeching cloud of dust.

But my favorite chore was what could be called the human-versus-chicken game of hide and seek that I played with the hens.

Most of the eggs were conveniently laid in the hen-house area, but Aunt Clara explained that biddy hens are endowed by nature to be super-secretive about where they made their nests and hatched their babies.

I got very good at my job. I stalked the wandering hens to their well-hidden nests and ignored their outraged squawking when I reached under their nestled posteriors to snatch a clutch of eggs.

* * *

Also in the “fond” chicken-house category are my memories of the farmers’ eternal war against the common sparrow (or “spatzie,” as my older cousins called them by their German name).

As cute and chirpingly charming as the sparrow is depicted in John James Audubon’s paintings, the farm boys see only infestations of disease-carrying lice hiding under those darling, fluffy feathers.

The farm’s chicken-house’s rafters were teeming every night with spatzies, which, in turn, were crawling with lice. The birds gotta go.

One autumn night, when I was very young, three of my Bartusek boy cousins rousted me from my comfy feathertick bed. They had declared war on spatzies, and I had been drafted into the troops.

That was so exciting! I was issued my weapon – a plain, wooden shingle that was wielded like a paddle.

The rules of war required us to blind the enemy with the flashlight beam. The spatzies would be panicked into flight, and we’d swat them down with our paddles, which were surprisingly efficient weapons.

All this yelling, crashing and thrashing scared the dickens out of the hens and set them all aflutter.

Aunt Clara opposed our murderous forays, not because she was a bird fancier, although she was a kindly soul and might have a soft heart toward the spatzies.

But, hell’s bells, now the super-agitated hens wouldn’t lay eggs again for the next 24 hours or longer.

Aunt Clara regularly sold the farm’s eggs every Saturday at Torrens Produce in Wahoo, and our war on spatzies resulted in less money in the family’s pocketbook.

Uncle Jerry wasn’t happy, either, at the wasting of flashlight batteries on such frivolity.

* * *

In Wahoo, as in any other rural Midwest town at that time, the lowly chicken played an important economic role.

We had the square-block-sized Blue Star Produce, an odorous chicken-slaughtering factory on the eastern fringe of downtown. It was one of the few industries bringing in dollars and jobs to Wahoo.

I got to thinking, why don’t I cash in on this poultry bonanza? I was about 10 years old, I’d been around chickens a lot, and I craved my own spending money. What could go wrong?

Besides, the Blue Star itself would unwillingly supply me with inventory, and for free! There were always a few flocks of wild chickens roaming the neighborhoods around the factory, escapees from the loading docks. I’ll just scoop them up and I’m in business.

I arranged with my Mom for the family restaurant, the Wigwam Café, to buy my produce. But I hit a snag when the wild chickens decided to remain wild, and could outrun me with ease.

Undaunted, I noticed that chickens couldn’t always outrun street traffic, so I picked up a couple of fresh roadkill whose intact feathers hid any carcass damage and took them to the Wigwam.

Mom agreed that they looked good. But, by the way, she asked, where did you get them?

(…Well, nice try, Bobby.)

* * *

However, Mom encouraged my entrepreneurial spirit and financed the purchase of a dozen live chicks from the Wahoo Hatchery. They were dyed different pastel colors, left over from Easter, but their feathers would soon outgrow the dyes.

I commandeered a doghouse in the back yard and staked out a chicken-wire fence around it. About 8 weeks later I produced edible broilers, as good or better than the Blue Star ever did. I don’t remember the price the Wigwam was going to pay me, but I’m sure it was fair market value.

It was early summer vacation time, and my parents had insisted that the whole enterprise was on my shoulders.

As much as I dreaded it, and we hadn’t really discussed it, I assumed the slaughtering was also my responsibility.

In my young life, I had witnessed countless killings of chickens. Aunt Clara, with grim determination and gritted teeth, would grasp the bird’s head around the neck. With a sudden strong, smooth spin of the wrist, the carcass would be flung a short distance away, and the head would still be in her fist. Nothing to it, right? It looked so easy.

Uncle Jerry, when he killed the bigger turkeys and geese, used an axe. One swift, sure chop did the job.

I went out one morning to survey with satisfaction the plump livestock that my hard work had produced. I thought I would finish the job and surprise my folks to do the killing all by myself. They’ll be proud.

So the die was cast.

I chose the neck-wringing option. It seemed quicker and less bloody. Stepping over the fence, I cornered the first unlucky pullet, which squawked and beat her wings mightily. I swallowed hard, grabbed her by the neck and gave her a tentative spin.

Big mistake! There should be nothing tentative about it. This was not like Aunt Clara’s example at all.

The intact hen landed at my feet, her neck awry, staring up at me with an accusing eye. I spun her around again, with the same useless result.

Panicking, I ran to the garage to get an axe. I wanted to use Uncle Jerry’s quick-kill method. Anything to get this nightmare behind both me and the chicken. But I managed to botch the third attempted murder, too.

The axe was heavy and I was a skinny little kid, so I had to awkwardly tuck the handle under my armpit and grip the iron blade way up front. I’d be lucky if I didn’t injure myself.

My eyes stung with tears. I brought the blade down as hard as I could on the struggling chicken's neck and ... chopped off her beak!

That set me really wailing. Mom heard the commotion from the house and rushed to help. She quickly dispatched that hen with an expert spin as good as that of her sister Clara’s, and together we finished off the rest of the flock.

As Mom pointed out that day, my education in neck-wringing overlooked an important detail: You must grip the fowl’s neck extremely tightly. I did not do that. The neck just spun ineffectively in my loose fist.

Who knew that? I sure didn’t.

That day, I swore I’d never put myself, nor any chicken, through that ordeal again.

And I’ve spent the ensuing 70-some years keeping that promise.