Hometown Hero.

Observations from attending Terence "Bud" Crawford's championship parade in downtown Omaha

My name is Chris Beaty and I am white. I've always been white. My parents are white, my neighborhood is white, and my friends growing up were white. (My kids actually aren't white, but that's a different essay). I'm kind of an expert at being white. My favorite sport is hockey. Mayonnaise and ranch are my go-to condiments. I've never been to a rap concert but have seen Lee Greenwood and The Beach Boys—neither on purpose but rather because those were the acts headlining two of my super white activities growing up. For a large part of my life I never put much thought into any of it.

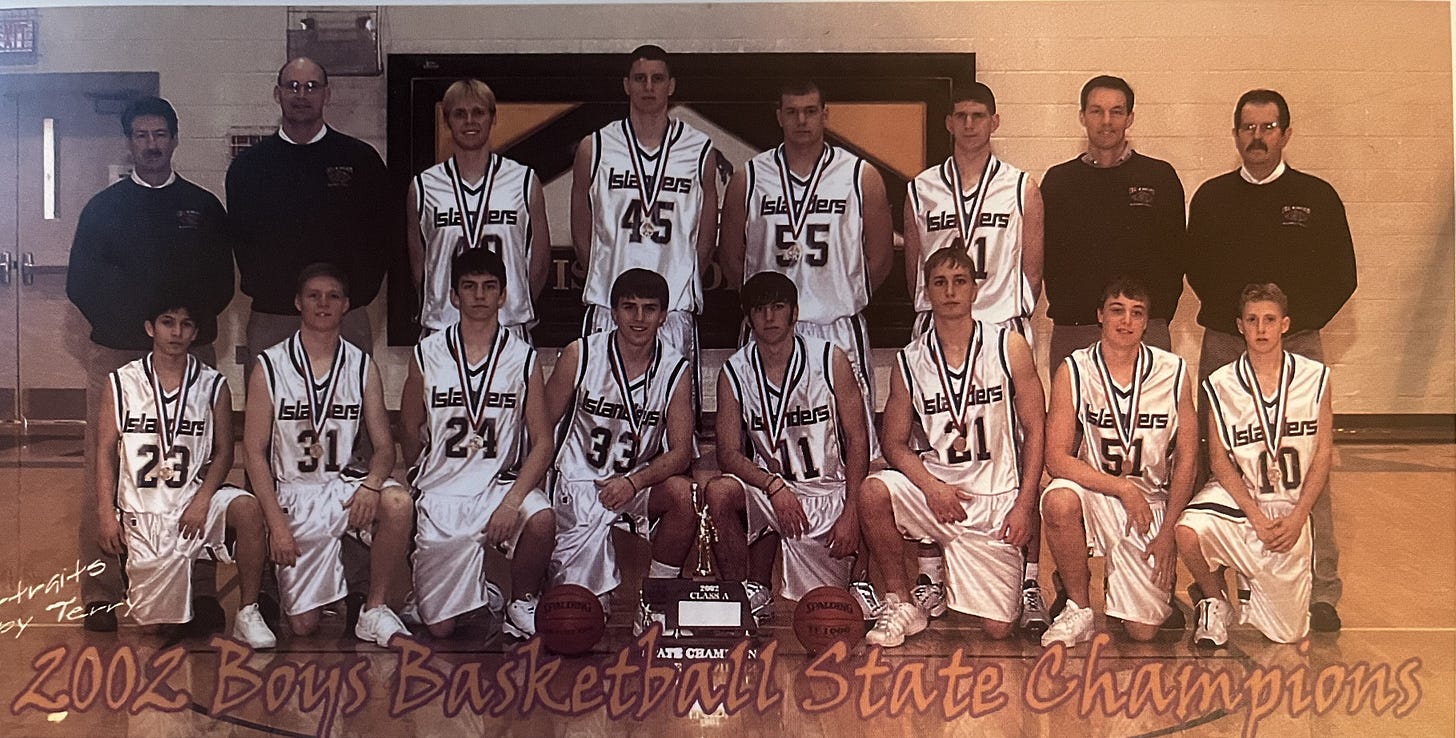

I live in Omaha, Nebraska along with a whole lot of white people. I grew up in Grand Island, Nebraska along with a whole lot of other white people. In high school, my friend Mike Beckton and I had this running joke when watching varsity boy’s basketball where we counted how many black kids were on each team and used that as the basis for deciding the game’s outcome. We called it the “black guy count” and the Grand Island Islanders were always at a significant deficit. Especially when we played a team from Omaha. In an era before analytics and Moneyball had taken over athletics, Mike and I were pioneers in using predictive statistics and applying them toward sports outcomes. It was pretty accurate too— Grand Island lost a lot of basketball games.

When I moved to Omaha for college, my life and environment changed drastically. In many ways the culture of Grand Island and Omaha could not be more different. People took pride in being from Omaha rather than lamenting how they got stuck in GI and wished they had moved a long time ago. People rallied around the College World Series and restaurants that appeared on Food Network shows rather than bitching about how rival-city Kearney got an Applebee's before we did. And I met kids my age that grew up in Omaha, decided to go to college in Omaha, and planned on living in Omaha afterward. By choice. This was unfathomable in Grand Island. But with all the excitement of the big city, there was still enough of home that was familiar and comforting. Husker football still united the town, even though it was miserable to watch. I could still buy sweet corn from the back of someone's pickup parked at the corner of a major intersection. I still ate a Runza on a monthly basis. And, well, the people around me felt familiar too. They were all white. This wasn’t on purpose—my freshman year I even joined a church group where my three closest friends were Chinese, Mexican, and black— but once I realized how sketchy that church was and moved on, so did those friendships. I started hanging out with white people again.

My perception of Omaha is limited to my experiences, and it takes a little while to realize your experiences aren't the same as everyone else's. To a local, all you need to say is “I live in West O” or “I live in North O” to drive this point home. West O is suburbia. West O is wealth. West O is where people pay for yard care and outsource hanging up Christmas lights. West O is white. I live in West O.

To someone who lives in West O, North O only comes up when someone tells you to “just avoid that area, especially at night.” North O is crime. North O is gangs. North O is drugs. North O is black.

How much this perception is true depends on who you ask and what kind of stories they have. But since most white people stay out of that part of town, the only stories they have are the bad ones that didn't happen to them—but rather happened to a guy they knew who heard it from a buddy of his cousin. If you get turned around trying to drive downtown and (God forbid) end up on Ames Street or Lake Street, you mutter “oh fuck,” lock the doors, and take the quickest side street you can find to head South.

How many people do I know that have actually had something bad happen to them in North O? Zero. But North O is still scary.

No one from West O really has any idea what North O is like.

•••

On May 25th, 2020 in Minneapolis an event happened that changed a lot of minds. I remember the hooded sweatshirts when Trayvon Martin was killed in Florida. I remember LeBron James wearing “I CAN'T BREATHE” clothing during warmups at some NBA game. I even wrote an essay defending Colin Kaepernick. But I barely remember these events. None of them upset my status quo. None made my life any different. All of these injustices were easy to fade into the background, because what it’s like to be black is completely lost on me. Because I’m not black.

George Floyd's death was different— it couldn’t be ignored. It was a rallying cry. A scream. When I visited my sister in 2021, I stopped by the site of Floyd’s murder outside of Cup Foods. The streets were blocked off by homemade barricades and 24-hour martial law prevented anyone from entering that didn’t treat the site with reverence. There was a sign at the entry reading “this is a sacred place.”

And it was.

This disruption revealed something. A reality that was too easily ignored because it was not the reality that I was confronted by day in and day out. But that didn't make it any less real. Like Neo in The Matrix, I was given the red pill and my eyes were opened. Just slightly. And they hurt because I had never used them before.

Omaha, like every major city, was in uproar. Protests necessitated citywide curfews and riot gear. One downtown bar owner killed a protester after a questionable confrontation— leading to a month-long controversy ultimately ending in the suicide of the bar owner pending his inevitable trial.1 Windows were smashed. Pepper spray was effused. Tear gas clouded the streets. One protestor suffered cornea damage when a pepper ball hit him in the eye.2

I stayed home.

•••

Enter Terence “Bud” Crawford.

I’ve never watched a boxing match. I don't even know if it’s called a “match.” Maybe it's a boxing “fight,” but I don't really know. I've seen all the Rocky movies, so I know the sport is ripe for a good against-all-odds-underdog story. The closest I’ve been to being an underdog is being a Nebraskan. I love being from Nebraska. I have no desire to live anywhere else, but people that aren’t from Nebraska are surprised to hear you admit that. They assume you’re a bit embarrassed. They feel safe making fun of your state. After all, “what’s there even to do in Nebraska?” But I’m proud of where I’m from, and when others show that same pride, I am proud they are from Nebraska too.

What happens when these two worlds collide? One that I know nothing about, and another I know everything about? It looks a little like a kid that grew up in North O becoming the greatest athlete alive. It looks like a shredded black man on ESPN highlights, wearing trunks that say “OMAHA” and a flat bill hat with the Husker “N” on it. I have no idea what makes a great boxer, but I know a great ambassador when I see it. And as more and more people told me how great Bud Crawford was, the more I saw him. And cheered for him. And was proud of him. He became unavoidable, and I started to care a little about boxing. Not so much the sport, but the boxer.

About every 6 months I heard about Bud's next fight against a guy that was supposedly really good. I would forget when the fight was, and then I would hear Bud won. Again. By knockout. It just kept happening. When he beat a guy named Errol Spence, Omaha got real excited because he had “unified” four belts. I still don't know how boxing works. I thought he was already the undisputed champion of the world, and I wasn't really sure how you could become even more undisputed. But people were pumped. Bud had united something people thought couldn’t be brought together. Something that seemed impossible— until Bud did it.

Omaha wanted to thank him, so the mayor threw him a parade. Since there are no professional sports teams in Omaha, we’ve never had a championship to celebrate. I had to go— I couldn’t stay home.

As I parked my car half a mile away from the end of the parade route, I heard the steady pulse of rap periodically interrupted by a guy on a mic yelling things in a cool way that got people riled up. I found a shady spot next to a man carrying a dog in a backpack and started sending text updates to my wife. With the exception of the guy with his head half-shaved exposing the tattoo of a marijuana leaf, I let my wife know that there were “not a lot of white people here.”

I didn't put any thought into who would show up to a Bud Crawford parade— and this wasn't your typical Creighton basketball crowd. I pieced together later that the parade organizers reached out to North Omaha and African American organizations to participate. They represented the community that supported Crawford throughout his career and they take ownership of where he came from. These are the kids that want to grow up to be just like him. The families that went to watch him before he was seen by a pay-per-view audience. And then there was me— the white guy from West O that just wanted to go to a parade. But I was still excited.

The parade planners wanted this event to represent a group of people that doesn't get a lot of representation. I had no idea how many step dancing groups were active in my city and hadn't heard of any of the black-owned food trucks parked on the curb. When Bud Crawford came out on a motorboat pulled by a pickup— I just smiled and shrugged. I wanted to ask the lady next to me carrying a fishing net to explain it to me, but I wasn't quite ready to out myself as completely clueless.

The parade route ended at an outdoor pavilion where a rally was supposed to follow. Everything was running behind schedule, but that didn't damper spirits. I bought a chocolate chip cookie. The man in front of me told the story of his nephew placing a considerable wager on Bud’s fight, and now he was buying a home in Seattle. There were a lot of ways to profit off of Crawford.

When the rally finally got underway, a woman belted out the Star-Spangled Banner followed by another who sang a gospel hymn. The event was MC'ed by the hosts of a sports radio show I had never heard of— but I recognized one of the personalities from his previous gig discussing Husker football in the morning drive timeslot on 1620AM. No one was in much of a hurry. One of the guys made the DJ play a pump-up rap song repeatedly so the crowd could sing the next line a cappella. It took several tries. I didn’t know the song, but everyone else did.

Mayor Jean Stothert had a history of supporting Bud Crawford, giving him a key to the city and sponsoring the day's festivities. I've consistently voted for her. She was introduced first and got a nice response, but from there the politics of the crowd became a bit more apparent. A chorus of boos ensued when Mayor Stothert handed the mic off to U.S. Senator Pete Ricketts— the former Governor, silver spooned, Trump-backed, heir to the TD Ameritrade trust fund (at least until his family sold the locally owned business for a fat payday while he was still in charge of the state's economy). Governor Jim Pillen didn't fare any better, and when Congressman Don Bacon was introduced, the first thing I heard was a loud “ahhh hell nah” shouted from the man behind me.

It wasn’t exactly their political base.

Only Congressman Bacon tried to use the moment for campaign purposes.

“I see Bud out there in the community because I'm out there with him!”

The comment didn't turn the volume down on his detractors and felt a bit desperate.

The next two speakers went smoother. One was a City Council member I didn't know, the other was a bureaucrat working in some public office that I didn't know. Both did a nice job. Both got a nice response from the crowd. Both were black.

The event had a noticeable lack of structure, but not a lack of hype. There were cool montage videos of fights I didn’t tune in for and congratulatory video messages from rappers I didn’t listen to. I knew who Shaguille O’Neal was though, his video was pretty cool. I started getting text messages from my wife about how all hell was breaking loose at home. I left and watched Bud's speech later on YouTube.

•••

Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation centered around the question: how much does man control his own fate? Aristotle also chewed on this one quite a bit. Both seemed to conclude: not a whole lot. Assert this notion today and it can come across as not only counterintuitive, but cruel. Who are you to tell me what I can and cannot do? Who are you to tell me my limits? Who are you to determine my destiny without my input? I don't think this is a black or a white thing, I actually think it's a uniquely American thing.

How does that resonate to a community that has been given little to affirm their worth and voice? What does it feel like to be from North O? I still don't know. But from what I heard on that hot afternoon as a microphone was passed from one excited person to another, growing up in North O seems to look a bit different than growing up in Grand Island, Nebraska.

People talked about Bud coming from a hard place— the same place much of that crowd came from— yet through hard work he was able to overcome and become something great. It's easy to understand why this hero got the parade and Pete Ricketts got the boos.

So what's the lesson? Work hard? That's at least what the banner leading one of the many step-dance troops advised me to do.

“No excuses. Do the Work.”

This theme was unavoidable. But there was another slogan on a different step-dance banner that struck me.

“With God on our side, we can't be beat.”

The road to success starts by submitting to a power greater than yourself. You can’t do it on your own.

Both slogans felt odd to me. I came from the world of competitive marching band where sloganeering was absent from our parade banners. I wasn't sure what the context of being “beat” was in reference to. Are there step-dance competitions decided by the hands of the Almighty? Probably not.

“No excuses. Do the work.” and “With God on our side, we can't be beat!” aren't truisms for a parade, they’re truisms for life. These slogans had little to do with inspiring kids to be good at booty-shaking and pounding on out of tune drums. They were meant to inspire youth to rise to something greater. But aren't the maxims at odds with one another? We were at a parade to celebrate someone who overcame unimaginable odds by growing up in the rough part of a rather unremarkable city in a rather unremarkable state. His surroundings dictated Terence Crawford couldn’t do what he did. But he did.

Then again, lots of people work hard. And there’s only one Bud Crawford. You need something more than just doing the work. You need something else on your side.

So which is it? Does it matter where you came from or not? Do you have to do the work, or just get God on your side? This is a bit of a stupid question. Of course both things can be true, but which truth do you embody? Which truth propels you? Which truth do you use to inspire? Which truth do you tell a bunch of kids growing up in a poor neighborhood that are daily confronted with racism and a lack of self-worth to make them feel their lives matter? Does the idea you are in charge of your destiny provide comfort when you see so many people around you, people you love and admire, in a setting that lacks so much? Or does the surrounding hardship illustrate that God isn't really on your side after all? Is it your fault? Or God’s? Or your fault for not getting on the side of God?

I think we all struggle with these questions at a certain level, but it's easier to ignore the implications when your life is easy. When it's always been easy. When no one has ever subtly or overtly made you feel like you were less valued because of something you can’t control.

I don't know which slogan I would put on my banner.

•••

“It’s not just me winning. We all win.3”

This was the headline on the Omaha World Herald newspaper the next day. This was Bud’s message. Bud represents all of us standing in that crowd.

I felt like an imposter most of that afternoon, but nobody tried to make me feel that way. The unfamiliar can be easily mistaken for the unwelcoming. When one of Bud's posse asked everyone in the crowd to hold up a number 1 index finger so he could take a selfie, I looked around to gauge if it was appropriate for me to take part. I wanted to be part of the moment, but I felt it wasn't meant for me.

Yet I was still there.

There is something unifying about sports. In Nebraska the same conversation about Husker football can be heard from my daughter's YMCA volleyball game, a comic bookstore, a dive bar in a farm town, and a boxing gym in North O. Our teams represent something greater than just the players on it. A boxer can become a symbol for more than just a guy good at punching people. Why do we sing “We are the Champions” when most of us did nothing to earn it? Is it because in a way—from the environment, to the people, to the community, to the cheer, to the fervor— We actually were a part of something?

It wasn’t lost on me that the last time a group of this size gathered in downtown Omaha, it was to protest the blind eye that society gives to a particular group of people. Now many of those same people were there in celebration of one of their own.

One of our own.

I don't know if that's progress or not, but it felt nice to see. And I have a feeling the guy standing next to me in the crowd smoking a roach would have agreed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killing_of_James_Scurlock

https://www.ketv.com/article/bystander-suffers-permanent-eye-damage-from-pepper-ball-during-omaha-protests/32748721

https://omaha.com/news/local/it-s-not-just-me-winning-we-all-win-thousands-turn-out-for-omahas-bud/article_73a704f0-355c-11ee-8079-2721ff20f5ef.html