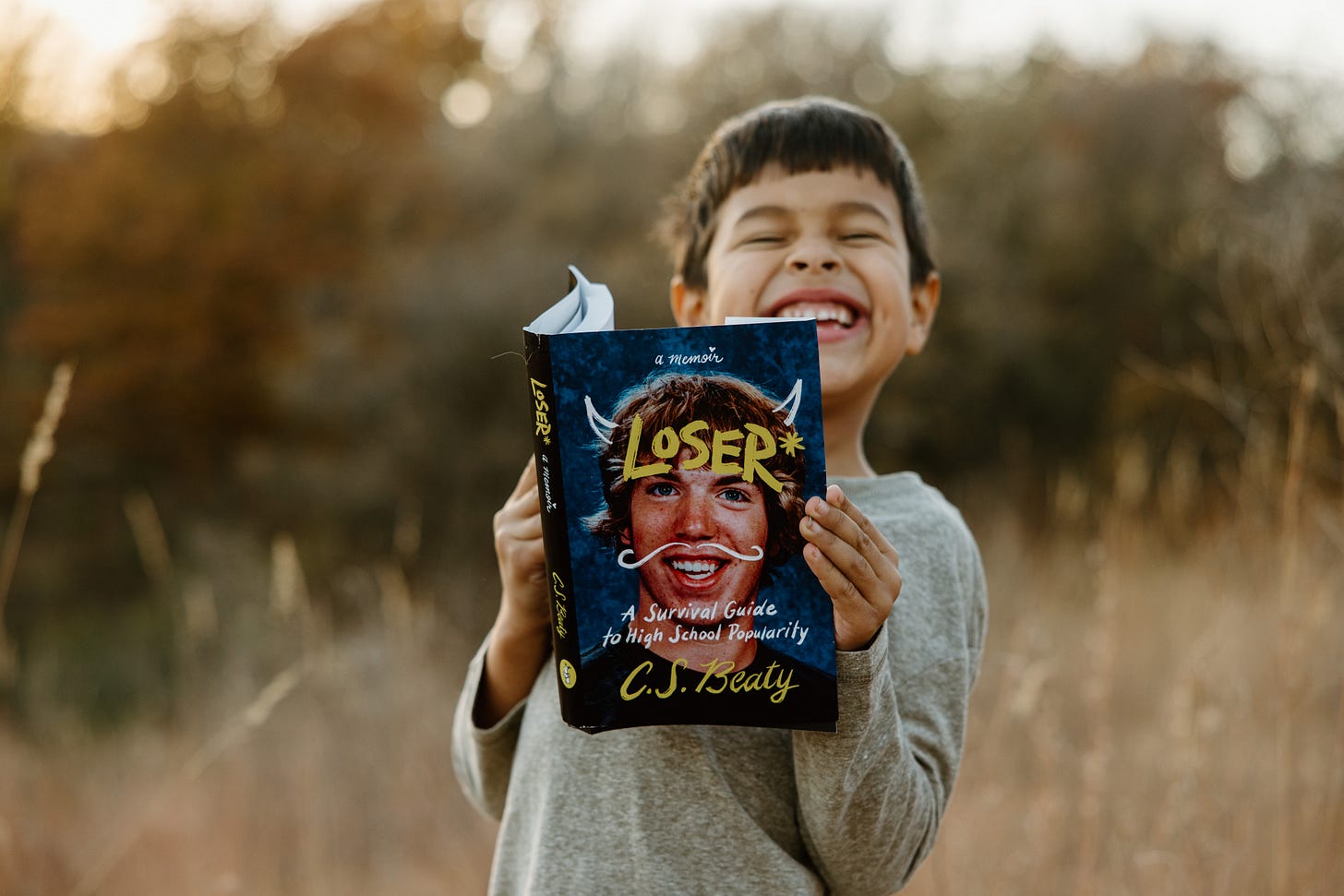

A few weeks ago I achieved a lifelong dream by publishing my first book. It’s a coming-of-age memoir about my awkward high school years—kind of like Sixteen Candles if that annoying kid who asked Molly Ringwald out on a date wrote a book about his life. As it turns out writing a book and selling a book are two different skillsets, and now that I’ve sort of figured out how to do the first one I’m now fumbling around on the second. The hard cover, paperback, and ebook are all out now on easy to find on my new website csbeaty.com— but I just started recording the files for the audio book. I wanted to share the first couple of chapters. It’s like the free chips and salsa at the Mexican restaurant that are designed to make you starve for the entree. Feel free to order the full meal.

What Just Happened?

I could never be at peace again till I had written my charge against the gods. It burned me from within. It quickened; I was with book, as a woman is with child.1

-C.S. Lewis

After the final dismissal bell rang, it was a long walk back to the band room.

My last class was English, which was a nice way to end things. I looked forward to those discussions even though I had little in the tank at 3:36 p.m. Mr. G.’s classroom was on the opposite end of the school from where I parked my red Isuzu pickup. The truck was a hand-me-down: handed down from a previous owner to my oldest brother, who then handed it down to my next oldest brother, who then handed it down to me. It had a manual transmission, no power steering, a different shade of red on each panel, and a threaded pipe welded to the tailgate where the original bumper had fallen off. I should have been embarrassed by this automobile forced on me by my parents, but I loved it. It was completely unlike all the starter cars my friends had been gifted, and it gave me an easy way to stand out from the masses—from my classmates whose personalities would melt together if left exposed to the high school environment for too long. It was nice to be forced to be a little different.

Like the rest of the kids in marching band, I had been at Grand Island Senior High before the sun had burned off the morning dew. The parking lot outside the band room was adjacent to the soggy grass fields where we soaked through tennis shoes while practicing marching drills. They always watered the lawn right before we showed up, which once led to our band director halting rehearsal and demanding the athletic director come outside to see what we had to put up with. I’m not sure it helped much. Marching band wasn’t exactly a priority at our school. I learned to pack a change of socks and stashed the soggy ones next to my winter coat in the back of the band room. Throughout all four years of high school, I never once bothered to learn where my locker was. Piling my things on top of these filing cabinets served my purposes just fine. No one messed with the drummers’ stuff piled in the back. The only kids who went into the band room were band kids, and the drummers were not to be fucked with. At least not to be fucked with by other band kids. Outside the walls of the band room we were prey, but within them we were lions.

Noah Woods and I walked side by side for the first half of the route until he exited the main doors to track down his car. Noah was one of my closest friends and probably the only person I didn’t try to prove myself to. I was pretty sure I hadn’t turned Noah into a Christian yet, but I was working on it. He had been to our church’s youth group a few times and even agreed to go on the church’s spring break trip to Denver with me. I was making progress and was determined to convert him—but frankly his lack of interest in his eternal damnation was starting to piss me off.

Noah and I had been friends since middle school when we bonded over watching sports and Quentin Tarantino movies. It was at Noah’s house where I finally finished watching Kill Bill: Volume 1. My mom let me rent it from Blockbuster several years earlier after I told her it was one of my older brother’s favorite films, but she insisted on watching it with me and powered down the DVD player when the opening scene centered around a male nurse selling Uma Thurman’s comatose body for sex to a trucker named “Buck who likes to fuck.” From all my mom’s years working at a hospital, this must have hit a little too close to home. Or maybe it was because I was thirteen at the time.

I passed the mural of our school logo painted over a concrete brick wall—a pair of luscious palm trees in front of a gorgeous sunset, beckoning us to a place far away from the corn fields of central Nebraska. Because of our nonsensical city name of Grand Island, our school and our town as a whole had an island motif forced on it. We were the Islanders, which only made slightly more sense than the Vikings at the nearby Grand Island Northwest High School. I suppose one school liked ships and the other liked where the ships docked, neither of which really fit with the landlocked scenery outside our high school windows. We gave our respective schools more appropriate nicknames: the Islanders would say the Vikings went to “Cow Pie High,” whereas the Vikings returned the favor by calling our school “Drive-by High.” Neither school’s administration accepted these write-in ballots for naming rights, but the monikers fit.

The “purple island” was ahead—a plywood mountain covered in carpet where the anime club kids played Magic: The Gathering. I considered making a pit stop at the nearby snack shack named Hula’s. Hula’s was run by the Special Education students and sold gallon-sized chocolate shakes for $1. Sometimes my mom would buy me a Hula’s punch card, which the workers with Down syndrome often forgot to punch. I probably should have told someone. I started going to Hula’s less and less after childhood obesity concerns reduced the serving sizes available in public schools. These changes devastated Hula’s business, and the impact was felt. I not only lost an easy 1200 calorie snack at the end of my day, but the lack of customers also made it harder to eavesdrop on the conversations of hot girls. I greatly missed the casual mentions about how “shaving your pubes if you’re a girl makes total sense, but I wouldn’t want my boyfriend to do it.”

Anxiety is my motor. In addition to saving the souls of my friends from eternal damnation, the toils of the day ended with a list of homework to be completed, activities to show up for, and work shifts to cover. And the doomsday clock on my time at high school was ticking. Where was I going to go to college? What was I going to study? How was I going to pay for it? Those questions dragged on my subconscious like seaweed building on a tow line. I felt I would get to those to-do items—eventually— but there were others I wasn’t so sure of. As the youngest of four kids, I knew the patterns. I had seen it play out three times ahead of me in the lives of my older siblings. You were supposed to leave high school with a stable of lifelong friends and an established love life. Granted, that’s not exactly how it played out for my sister or either of my two older brothers, but that was how it was supposed to work. I needed to make friends who could be my groomsmen on the day I married my high school sweetheart— but for some reason we were all just kind of shitty to each other.

I entered the main corridor where all five of the school wings met in a central spillway. Any hopes of catching up with my friends would have to be put on hold, as the halls were now deafening with Islanders fleeing from captivity. During my high school orientation, I was taught to hold up my hand with fingers splayed to get a rough idea of the layout of Senior High’s floorplan. The 500 wing was the thumb, the 400 wing the index finger, and so on. I was now in the center of the palm, along with two-thirds of the school body, half-way to the ring finger where I could exit the fingernail to reach my pickup.

I took the long route to avoid seeing Mike Beckton. Mike is my best friend. And I hate him. We did everything together, which meant his car was parked next to mine from early morning drumline practice. I wasn’t mad at Mike, I never really was, but we were overexposed. There was a constant comparison between us in the eyes of the Grand Island Senior High social elites. I was smarter than Mike and arguably better at drums—but that didn’t translate to popularity. Mike unfairly compensated for his faults by being confident. I never knew if Mike felt like we were competing. He never acted like it when we hung out. But then again, neither did I.

Mike and I even dressed the same, the only difference being that the taco seasoning body odor smell of my black drumline hoodie was mixed with the sulfur of gun smoke. I was on the trapshooting team. Mike played soccer. We both owned black studded belts purchased from the recently opened Hot Topic at the Conestoga Mall and had grown our hair to shoulder length to the chagrin of our parents. Our t-shirts were carefully selected from the undersized options of esoteric bands. Some of my shirts fit better than others—I never knew what size to wear since my body was constantly going back and forth from pudgy to skinny based on the timing of growth spurts. Mike and I both wore skateboard shoes despite the fact that neither of us knew how to skateboard. He usually chose DC as his brand of choice, though I had worn Vans ever since my older brother bought a pair. I never got into wearing girl jeans like Mike, though. I tried a pair on once with him at American Eagle. He bought them. I didn’t. But I did make the mistake of telling Alexa Whitney my girl jeans size and successfully made her hate herself.

I was almost out of the school. I passed the bench where I drank a pint of chocolate milk from a vending machine each morning and rounded the corner into the fine arts section of Grand Island Senior High. The band room was adjacent to the choir rooms, which meant I had to dodge the awkward theater and show choir losers before joining my fellow band geeks. However, there was one member of the show choir I never minded seeing. In fact, it was my favorite part of this route each late afternoon. Right before pounding through the crash bars of the band room door and presenting myself to my fellow musicians like Kramer entering Jerry Seinfeld’s apartment—I smiled and said “oh hi” to Jackie Wilkerson. Seeing her blonde hair and bright eyes was the highlight of this walk. Maybe the highlight of my entire day. I always wanted to say something more to Jackie, but then again, she never said much more to me. But we were both there. Each afternoon. For that One. Brief. Moment.

The exchange was always over fast. Too fast. She knew she couldn’t enter the band room, and I knew I wasn’t allowed to fraternize with the choir kids not that either of us wanted to. Capulets and Montagues don’t mix.

But we both seemed to like seeing each other.

There she was. Her feet shuffled a bit to slow down her pace. She gave her customary smile and greeting—and I returned the favor with a smile and fake surprise of my own. But as I pulled away to exit the hall, something broke the pattern. Jackie paused. She hesitated for just a moment.

And Jackie Wilkerson kissed me square on the cheek.

I stood in the corridor frozen in place, but Jackie kept moving. When I thawed, I looked over my shoulder to locate my favorite soprano. All I could see was her blonde ponytail fading into a crowd of highschoolers like a shark fin sinking back into the ocean.

C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces, (Geoffrey Bles, 1956), 247.