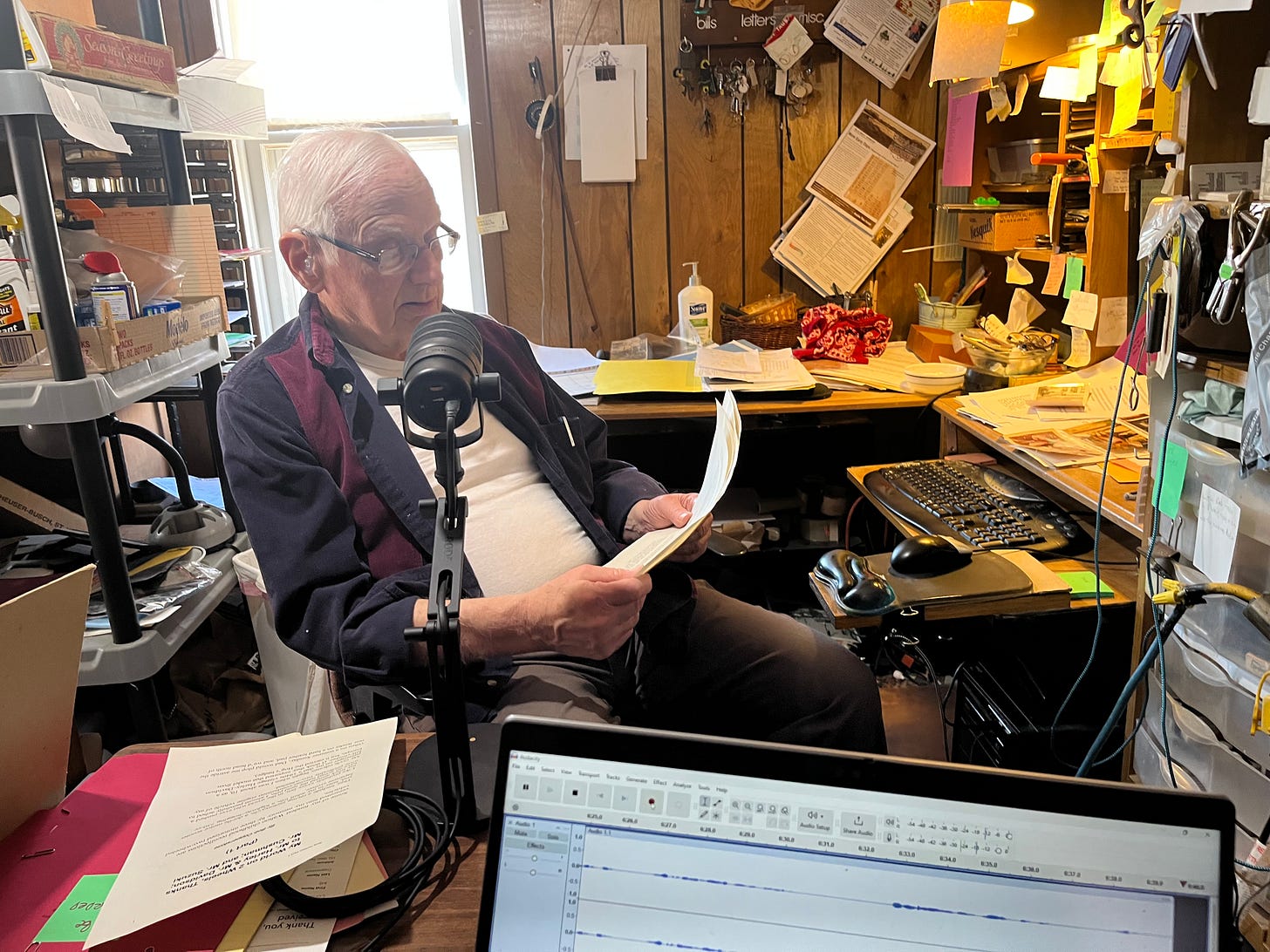

By Bob Copperstone

Hi, folks: I'll share with you some fond memories of harvest time on the farm.

I know that most of you were never farmers. Me, neither.

But thanks to my Aunt Clara and Uncle Jerry Bartusek, the seeds of farm memories were planted deeply into my young mind, and I am gleefully reaping their harvest today.

Here is my take on the memories, written for the upcoming newsletter of the Saunders County Nebraska Genealogy Seekers (Gen Seekers).

Farm Harvest Memories

My favorite adventures as a young boy were not at any sleepover camp, but at my Aunt Clara and Uncle Jerry Bartusek’s farm, especially during harvest time.

Often, I and my sisters, Rochelle and Janie, went there in the summertime, when we were set to work

Bringing in the harvest bounty took a lot of sweat and toil out of this pre-teenager. But I realize today that the work ethic learned on the farm helped me as I morphed into adulthood.

The farm was just north of Ceresco. It skirted the old Highway 77 stretch that was abandoned to become a gravel road because the new highway had shifted further east on its way to Wahoo.

Like hundreds of other farm dwellers in Saunders County, Clara and Jerry and my older male cousins would come to Wahoo on Saturdays to buy groceries, visit and gossip, drink beer, play pool, and watch the livestock auctions at the Sale Barn down by the Fairgrounds.

At the close of any Saturday night, I had the option of hitching a ride to the farm and staying for a week or more. Whenever I took that opportunity to break the monotony of a long summer vacation in town, I knew I would be put to chores from the time of the rooster’s first crow until I dropped bone-weary into one of Aunt Clara’s feathertick beds.

My stern Uncle Jerry, who always scared me and my young cousins a little bit, seemed to tolerate me when I grew older. At least he didn’t scowl at me too much as I became a useful farm laborer.

I learned later that Jerry (originally Jarislav), as a young immigrant from Moravia in Eastern Europe, had survived really tough times there, as well as in America. To boot, he was a Great Depression survivor during the “Dirty Thirties.” By the time I came along, he had hardened into a taciturn, gruff man with the weight of the farm’s survival on his back, who did not suffer little children lightly.

Later, after I quit being a child, I was startled and delighted to discover him to be a friendly, delightful man with a quick, roaring laugh. I had to keep reassuring myself that he was, indeed, the same scary, scowling Uncle Jerry.

I stayed at the farm most any time of the year, but it was during harvest that I was most useful, worked hardest, and remember best.

The toughest chore for me was shocking the oats crop. The farm still worked horses at the time, so part of the bottom northeast field was planted in oats. The grain would either be fed to horses or sold.

Using ancient cast iron mowers, rakes, binders and other equipment that lay unsheltered in the fields since last year’s harvest, Uncle Jerry cut the crop (1st step), raked it into windrows (2nd step), bound them into bundles (3rd step) and laid them on the ground.

Shockers (that’s my cue) would then gather three or more of the twine-bound bundles together (4th step) and stand them up into small tepee shapes in order to keep them dry and await the threshers (5th step). The grain heads would rot on the ground if they weren’t shocked into rain-shedding position, which also made them easier to pick up for threshing.

We would spend all day in the ripened fields under the burning sun. Lunch breaks were welcomed, and we’d trudge back to the farmhouse for Aunt Clara’s cooking. During harvest, she toiled nearly non-stop over her hot kitchen’s cast iron, cob-burning stove. She’d churn out four meals a day, one after another, to fuel the harvest crew -- breakfast at sunup or before, lunch about 9:30, dinner at 2, and supper at sundown.

Soon enough, we were finished shocking and had the oats prepared to be brought in. The following Saturday, I rode with the farm family back to Wahoo. I was a thoroughly work-wearied young boy by this time, but I carried with me a satisfied sense of a harvest job well-done. It had felt good working side-by-side with adults who considered me their equal at the chore, smiling approval at my efforts. Uncle Jerry even gave me a bit of a grin as I got out of the car and said my good-byes.

That serene sense of accomplishment would linger with me until the following autumn, when the call of the harvest would again beckon me to “go out and shock them oats.”

Fragrant Cattle & Café Stir Sale Barn Memories

Today, Lee Maly’s Branding Iron Café is a popular place at the livestock auction site near the Saunders County Fairgrounds.

But I wonder who remembers the building’s roots in mid-century Wahoo.

As a small boy I and my cousin Gary Kracman used to poke around on Saturdays. We called it simply the Sale Barn.

On weekdays I would dig for earthworms in a ditch on the west side of the buildings to bait my hook for bullheads in Sand Creek near Dance Island.

Saturdays were big deals at the Sale Barn when farmers would buy and sell livestock, chat with neighbors, talk crops, get breakfast or lunch, and watch the auctions.

* * *

This is where today’s Branding Iron Café building intersects with my childhood’s oral history.

Since perhaps 70 years ago, the wooden superstructure shell of the building has not held livestock but mostly was for storage.

The building nearest east First Street in front of the actual auction barn itself originally was open at both ends, kind of like a corncrib, with a pathway down the middle and individual stalls along each side. Farm wives would use the stalls to display their baked goods, dressed or live chickens and eggs, along with other household yard-sale type items.

After the auctioneers finished selling livestock, they would move the sale to the front building, walking down the aisle and selling from the stalls.

Hardly a trace of the building’s livestock past remains today, from floor to roof. And that’s a good thing -- there’s enough built-in nostalgia for its cafe past to be worthy of preservation.

I like the idea of the Branding Iron’s location, smack in a rural atmosphere that bespeaks hearty farmers’ and cattlemen’s hard toil and sharp appetites.

That’s probably why one of the state’s famous restaurants, Johnny’s Café in Omaha, has been able all these years to attract customers to dine in the same neighborhood as the once-fragrant Omaha Stockyards.

Today, what’s left of me and my childhood applaud Lee Maly and her worthy business enterprise in Wahoo.